The AUGUSTUS trial was a large, prospective, randomised trial with a two-by-two factorial design that showed that AF patients with recent ACS or PCI who used a P2Y12 inhibitor and apixaban had significantly less bleeding compared with warfarin (10.5% vs 14.7%, respectively; P<0.0001) [2]. No significant difference was seen between patients who received additional aspirin versus placebo in the secondary outcomes of composites death or hospitalisation and ischaemic events: death or ischaemic event for apixaban versus VKA (6.7% vs 7.1%; P>0.05); death or hospitalisation for aspirin versus placebo (26.2% vs 24.7%; P>0.05); death or ischaemic event for aspirin versus placebo (6.5% vs 7.3%; P>0.05); ICH for apixaban versus VKA (0.2% vs 0.6%; P>0.05); ICH for aspirin versus placebo (0.4% vs 0.4%; P>0.05).

The objective of this post-hoc secondary analysis, presented by Prof. John Alexander (Duke University, USA) was to explore the balance of risk (i.e. bleeding) and benefit (i.e. ischaemic events) between randomisation and 30 days, and between 30 days and 6 months, with aspirin and placebo, in a cohort of 4,614 patients enrolled in AUGUSTUS. Although the choice of P2Y12 inhibitor was left to the treating physician, more than 90% of the patients were treated with clopidogrel, which is consistent with most guidance statements.

From randomisation to 30 days, the risk of severe bleeding was 2.1% with aspirin versus 1.1% with placebo (absolute risk difference 0.97%; 95% CI 0.23-1.70). Severe ischaemic events occurred in 1.7% patients on aspirin versus 2.6% on placebo (absolute risk difference -0.91; 95% CI -1.74 to -0.08). From 30 days to 6 months, the risk of severe bleeding with aspirin was 3.7% versus 2.5% with placebo (risk ratio 1.25; 95% CI 0.23- 2.27) while the risk of severe ischaemic event was 3.8% versus 4.0%, respectively (absolute risk difference -0.17; 95% CI -1.33 to 0.98).

Prof. Alexander pointed out some limitations of the study, such as patients receiving aspirin prior to randomisation (median 6 days) in both arms, which could have influenced subsequent bleeding or ischaemic outcomes. Also, severe, intermediate, and broad composite bleeding and ischaemic event outcomes may not be of completely comparable severity, and the number of events was small, especially regarding the more severe outcomes.

In conclusion, apixaban with or without aspirin seems to balance the bleeding risk with possible ischaemic benefit in the first 30 days of treatment; continued aspirin is associated with more bleeding.

- Alexander JH, et al. Abstract 409-08. ACC/WCC 28-30 March 2020.

- Lopes RD, et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1509-1524.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Homozygous FH responds to alirocumab Next Article

Recombinant factor VIII safe and effective in PUPs A-LONG study »

« Homozygous FH responds to alirocumab Next Article

Recombinant factor VIII safe and effective in PUPs A-LONG study »

Table of Contents: ACC/WCC 2020

Featured articles

Heart Failure and Cardiomyopathies

Mavacamten shows promising results in non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Vericiguat shows beneficial effects in a very high-risk HF population

No role for sodium nitrite in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Vascular Medicine and Thromboembolism

Rivaroxaban and aspirin effective and safe for PAD patients

TAILOR-PCI misses endpoint but still provides valuable insights

Edoxaban: alternative to warfarin after surgical aortic or mitral valve procedures?

Bleeding reduction post-TAVI with OAC alone vs OAC + clopidogrel

Apixaban offers new perspective for cancer patients in need of anticoagulation

Rivaroxaban superior to enoxaparin in preventing VTE in non-major orthopaedic surgery

Interventional Cardiology

TAVR safe and effective in low-risk bicuspid aortic stenosis patients

TAVR model reveals differences in hospital outcomes

2-year results show non-significant outcomes TAVR vs surgery in severe aortic stenosis

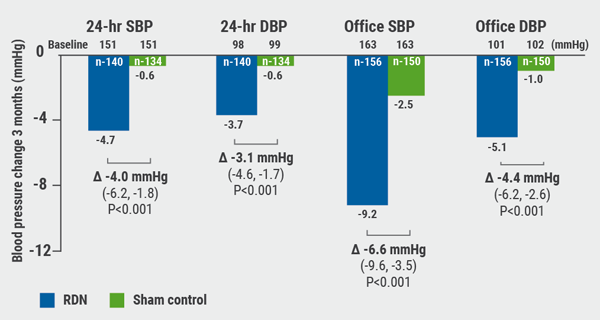

Renal denervation better than sham for blood pressure

Infusion of ethanol in the vein of Marshall for persistent AF

Atrial Fibrillation/Acute Coronary Syndrome

Fewer adverse events with ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months DAPT

TWILIGHT sub-study: same outcomes for diabetes patients

TWILIGHT sub-study: complex PCI patients

LAAO Watchman registry data positive

Apixaban in AF patients with recent ACS/PCI: Drop aspirin after 30 days

Genetics and Prevention

Homozygous FH responds to alirocumab

Evinacumab significantly reduces LDL-C in homozygous FH patients

Higher serum levels of eicosapentaenoic acid correlate with reduced CV events

Quit smoking: vaping + counselling helps

Related Articles

September 5, 2020

ACC.20/WCC Highlights Podcast Part 2 of 3

September 8, 2020

Radial artery best for second bypass

September 8, 2020

Renal denervation better than sham for blood pressure

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com