Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a rare, but progressive, and ultimately fatal disease. After decades of clinical trials which failed to identify an efficacious treatment regimen, two phase 3 trials with positive results were published in 2011 [1, 2]. The introduction of these two drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, meant that for the first time IPF patients had two treatment options that could reduce disease progression. During the ERS meeting [3] and in a quite recent review article [4], Prof. Ganesh Raghu (University of Washington, USA) summarised the key lessons to be obtained from the clinical trials that led to the current international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of IPF [5].

“Recent trials have focused on targeting a molecule or pathway, based on the pathological plausibility of that strategy”, said Prof. Raghu at the beginning of his lecture. The pathogenesis of IPF is characterised by fibrosis due to chronic injury and aberrant wound healing. It includes the following mechanisms: innate immune activation and polarisation, fibroblast accumulation and myofibroblast differentiation, or extracellular matrix deposition and stiffening. These aspects include putative targets of recently developed and studied drugs for the treatment of IPF [6, 7]. In the past 25 years, many trials have been performed using pharmacologic interventions based on biologic plausibility. Notable inclusions were interferons, etanercept, prednisone/azathioprine/N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), monotherapy with NAC, endothelin receptor antagonists, simtuzumab, and monoclonal antibodies (e.g. anti-IL-4/-13). Unfortunately, most of them failed.

Pentraxin-2 stabilises walking distance

Prof. Raghu mentioned some recent RCTs with positive results, beginning with a trial evaluating the effect of recombinant human pentraxin-2 (rhPTX-2) infusions every 4 weeks vs placebo in patients with IPF. Pentraxin-2 (PTX-2) is an innated immune regulatory plasma protein and member of the short pentraxin family of proteins. It binds so-called danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which have specificity for damaged tissue, and acts upstream in the fibrosis pathway. The PTX-2-DAMP complex binds to the receptor for the Fc portion of IgG (FcγR) on monocytes and macrophages, blocks fibrocyte and profibrotic/proinflammatory macrophage production, and modulates the fibrotic microenvironment. A recently published phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT evaluated the effect of rhPTX-2 vs placebo on change in forced vital capacity (FVC) in patients with IPF [8]. Of 117 randomised patients, 116 received at least 1 dose of study drug (mean age 68.6 years; 81.0% men; mean time since IPF diagnosis 3.8 years), and 111 (95.7%) completed the study. The least-squares mean change in FVC percentage of predicted value from baseline to week 28 (primary endpoint) in patients treated with rhPTX-2 was significantly less for those in the placebo group (-2.5 vs -4.8; P=0.001).

In contrast, no significant treatment differences were observed in secondary endpoints, including:

- total lung volume (difference 93.5 mL);

- quantitative parenchymal features on high-resolution CT (normal lung volume difference -1.2%);

- interstitial lung abnormalities difference 1.1%; and

- measurement of diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO; difference -0.4).

- Patients treated with pentraxin had a more or less stable walking distance compared to baseline. Specifically, at week 28 the change in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) was -0.5 metre for patients treated with rhPTX-2 vs -31.8 metre for those in the placebo group (P<0.001). “This is to my awareness the first clinical trial over the last 25 years to show stabilisation in the 6MWD as a result of IPF treatment”, said Prof. Raghu. RhPTX-2 was well tolerated, with no notable difference in AE rate between the two treatment groups [8]. The most common AEs in the rhPTX-2 vs placebo group were:

- cough (18% vs 5%);

- fatigue (17% vs 10%); and

- nasopharyngitis (16% vs 23%).

This trial supports further evaluation of the efficacy and safety of pentraxin in patients with IPF.

- Noble PW, et al. Lancet. 2011;377:1760-9.

- Richeldi L, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1079-87.

- Raghu G. Abstract 1522 ERS 2018.

- Raghu G. Eur Respir J. 2017;50. pii: 1701209.

- Raghu G, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:e3-19.

- Ahluwalia N, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:867-78.

- Duffield JS, et al. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:241-76.

- Raghu G, et al. JAMA. 2018;319:2299-2307.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Landmark triple therapy trials Next Article

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma »

« Landmark triple therapy trials Next Article

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma »

Table of Contents: ERS 2018

Featured articles

Letter from The Editor

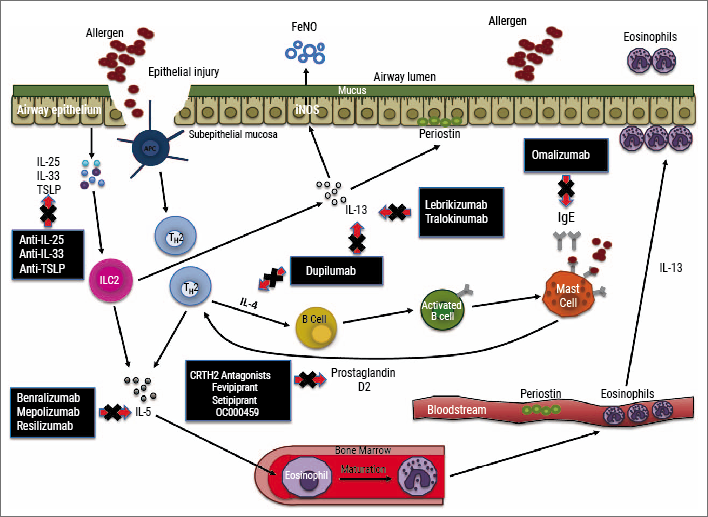

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma

COPD: Triple Therapy, MABA and Antibiotics

Landmark triple therapy trials

ICS: to use or not to use?

MABA, and novel LAMA

Macrolide antibiotics and trial with azithromycin

Current Look on Asthma

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma

Endoscopic Solutions

Endoscopic treatment of emphysema

Endoscopic treatment of asthma

Endoscopic treatment of chronic bronchitis

PAH

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for CTEPH

New therapeutic targets: moving form pre-clinical data to phase 2 studies

IPF

Gastroesophageal reflux, IPF and lessons learned

Oncology

ALK inhibition, guidelines, liquid biopsies, and immunotherapy

Brain metastases, lung cancer and interstitial lung disease

Related Articles

November 7, 2018

ALK inhibition, guidelines, liquid biopsies, and immunotherapy

November 7, 2018

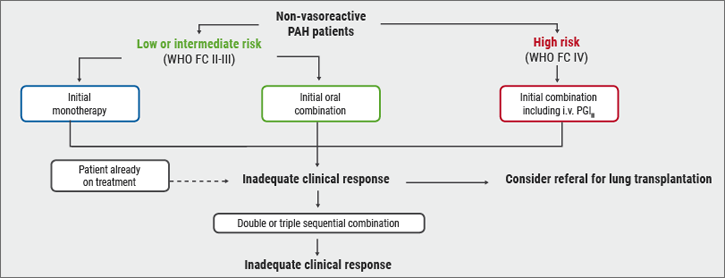

Risk stratification

November 7, 2018

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com