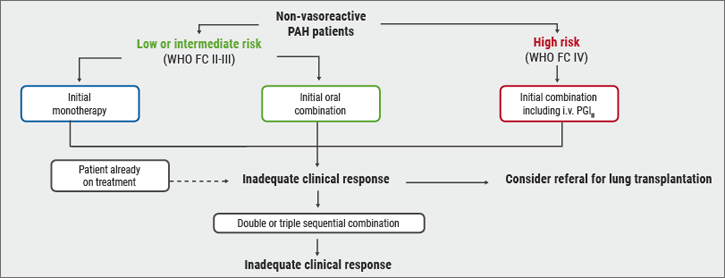

Risk stratification is fundamental for the determination of optimal treatment strategy in PAH. According to the ESC/ERS guidelines, the choice of the initial PAH therapy is dependent on the risk of the patient (see Figure 1) [1]. “For patients with low or intermediate risk (WHO functional class II-III), we have to consider initial monotherapy or initial oral combination therapy”, stated Prof. Olivier Sitbon (Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris-Sud, France) with regard to the guideline recommendations. “High risk patients (WHO functional class IV) should be treated with initial combination therapy, including intravenous prostacyclin analogues. We have to reassess the risk on therapy regularly, at least 3-6 months after initiation of the first-line therapy, and regularly during the course of the disease.”

Figure 1: Risk stratification according to the ESC/ERS guidelines about PAH [1]

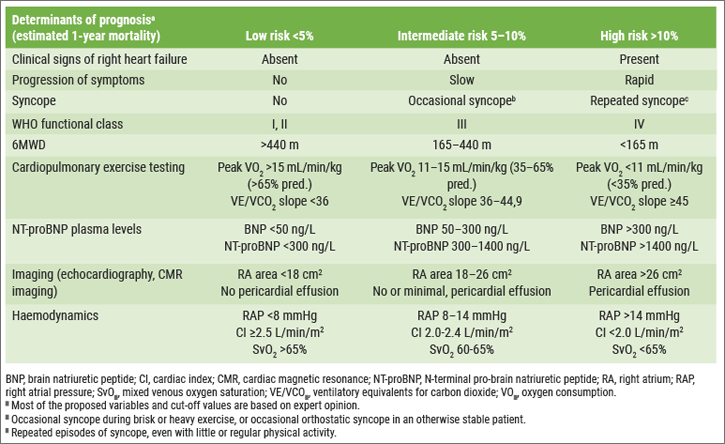

A "very famous" table of the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines divided patients into 3 risk groups based on some clinical variables, imaging, functional tests, and biomarkers (see Table). “So, functional class is not enough to stratify patients. We have to do a multi-parameter assessment. This table is based mainly on expert opinions, because we don’t have large studies.”

Table: Risk assessment (1-year mortality risk) in PAH according to the 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines [1]

Obtain a low risk status!

According to the ESC/ERS guidelines, the goal of treatment in all PAH patients is to achieve a lower risk status during the course of the disease [1]. “The class of this recommendation is very good, class I, but the level of evidence is quite weak, only C, because we don’t have prospective studies to demonstrate this.” Findings of Swedish [2] and pan-European PAH registries [3] suggest that comprehensive risk assessments and the aim of reaching a low risk profile are valid in PAH.

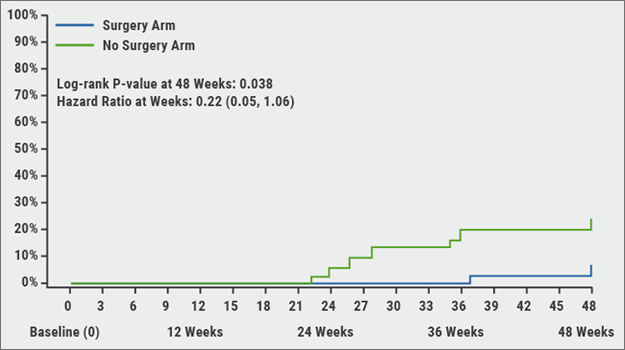

Figure 2: Relationship between risk profile at follow-up and long-term survival rates in the SPAHR and COMPERA registries [2, 3]

Obtaining a low risk status at 1 year is associated with a good prognosis, irrespective of the risk status at baseline [2]. “So, this methodology works to determine the risk status at baseline and at follow-up. Importantly, by lowering the risk it is possible to improve the prognosis of the patient.” However, in the two registries it was found that around 75% of PAH patients did not achieve a low risk profile at follow-up [2, 3]. “This could be due to the age of these patients,” suggested Prof. Sitbon “as the median age in the COMPERA registry was 70 year.” A recent publication of two Swedish registries, i.e. SveFPH and the earlier mentioned SPAHR, confirmed the impact of age and comorbidities on risk stratification, showing that most older patients (age >75 years) have an intermediate risk [4]. In addition, a retrospective study from the French pulmonary hypertension registry (n=1,017) found an association between the number of low risk criteria, both at baseline and at follow-up, and survival [5]. The researchers analysed 4 low risk criteria: WHO/NYHA functional class I or II, 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) >440 metres, right atrial pressure <8 mmHg, and cardiac index ≥2.5L/min/m2.

Improved long-term outcomes

The study by Boucly et al. showed that achievement of multiple low risk criteria is associated with improved long-term outcomes [5]. This effect was more evident at follow-up. The number of non-invasive low risk criteria at follow-up was also associated with prognosis [5].

In another analysis, published in Circulation, the French researchers found that the stroke volume index (SVI) and right atrial pressure were the haemodynamic variables that were independently associated with death or lung transplantation [6]. Finally, Prof. Sitbon mentioned another approach to estimate survival at 1 year in PAH patients: the REVEAL score. In this score, next to the 4 low risk parameters, also the subtype of PAH and some comorbidities are included. This score has shown a quite good discrimination with respect to the survival at 1 year [7, 8]. REVEAL identifies 3 good prognostic factors: improvement in BNP level, improvement of 6MWD and improvement in WHO/NYHA functional class.”

- Galiè N, et al. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:67-119.

- Kylhammar D et al. Eur Heart J. 2017 Jun 1.

- Hoeper MM et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2).

- Hjalmarsson C et al. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(5).

- Boucly A et al. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(2).

- Weatherald J et al. Circulation. 2018;137:693-704.

- Benza RL et al. Circulation. 2010;122:164-72.

- Benza RL et al. Chest. 2012;141:354-362.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Endoscopic treatment of emphysema Next Article

Letter from the Editor »

« Endoscopic treatment of emphysema Next Article

Letter from the Editor »

Table of Contents: ERS 2018

Featured articles

Letter from The Editor

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma

COPD: Triple Therapy, MABA and Antibiotics

Landmark triple therapy trials

ICS: to use or not to use?

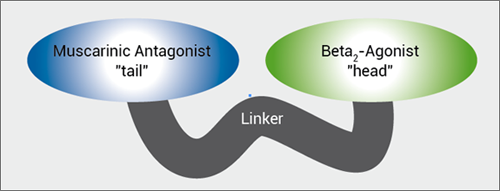

MABA, and novel LAMA

Macrolide antibiotics and trial with azithromycin

Current Look on Asthma

[Long Read] Current Look on Asthma

Endoscopic Solutions

Endoscopic treatment of emphysema

Endoscopic treatment of asthma

Endoscopic treatment of chronic bronchitis

PAH

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for CTEPH

New therapeutic targets: moving form pre-clinical data to phase 2 studies

IPF

Gastroesophageal reflux, IPF and lessons learned

Oncology

ALK inhibition, guidelines, liquid biopsies, and immunotherapy

Brain metastases, lung cancer and interstitial lung disease

Related Articles

November 7, 2018

Macrolide antibiotics and trial with azithromycin

November 7, 2018

Gastroesophageal reflux, IPF and lessons learned

November 7, 2018

MABA, and novel LAMA

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com