Dr Neal Bhatia critically discussed the use of oral antibiotics for acne vulgaris [10]. The majority of published guidelines and consensus statements support antibiotic use for inflammatory acne to limit proliferation of P. acnes on the skin. Tetracyclines are recommended as “first-line” agents. However, the use and duration of antibiotics should be limited due to antibiotic resistance concerns [11].

As Dr Bhatia pointed out, dermatologists use more oral antibiotics per prescriber than any other medical specialty, with the main indication being acne vulgaris. Dr Bhatia proposed a more critical use of antibiotics. Systemic antibiotics are only recommended in the management of moderate and severe acne and forms of inflammatory acne that are resistant to topical treatments [11]. Monotherapy should be avoided, and use should be always combined with topical therapy (e.g. retinoids or BPO).

A current publication also deals with measures to limit the development of antibiotic resistance associated with oral antibiotic use for acne. The authors recommend avoiding oral antibiotics when other effective options are available, limiting the use of systemic oral antibiotics to three to four months, and considering sub-antimicrobial doses of antibiotics with anti-inflammatory action, such as doxycycline [12].

Novel tetracycline effective in acne

A novel antibiotic, sarecycline, in the tetracycline family is in clinical development for the treatment of moderate-to-severe inflammatory lesions of acne vulgaris and has been shown to be highly effective in acne treatment.

“A promising characteristic is its limited activity against enteric gram-negative species. In contrast to traditional members of the tetracycline class, sarecycline does not affect the gut microbiome,” said Dr Leon Kircik of the Indiana University School of Medicine [13]. This could translate into a better gastrointestinal tolerability.

He presented pooled data from two identical randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled, Phase 3 studies. The studies comprised 2,002 patients (mean age 19.9 years) with moderate-to-severe facial acne. All patients had an IGA score ≥3 as well as 20–50 inflammatory lesions, ≤100 non-inflammatory lesions, and ≤2 nodules. The patients were randomised and treated with sarecycline 1.5 mg/kg/day, or placebo, for 12 weeks.

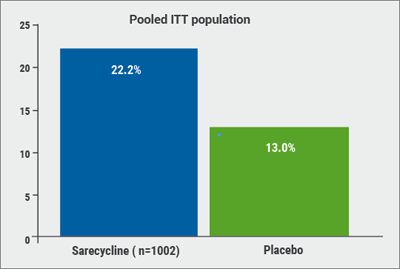

Of the patients were treated with sarecycline, 22.2% experienced a ≥2-grade improvement on the IGA and a score of 0 (“clear”) or 1 (“almost clear”) skin at the end of 12 weeks (defined as therapeutic success), compared with only 13.0% of patients taking the placebo (P<0.0001; see Figure). In addition, inflammatory lesions at Week 12 were reduced by 50.4% among patients taking sarecycline and 34.7% among those on placebo (P<0.0001). Starting at Week 3, sarecycline was statistically superior to placebo for inflammatory acne.

Figure: Significantly more patients treated with sarecycline gained therapeutic success (a ≥2-grade improvement on the IGA and a score of 0/1) compared to placebo. [13]

A post hoc analysis of patients with more than ten non-inflammatory lesions at baseline revealed a reduction of 34.8% in the number of non-inflammatory lesions at Week 12 with sarecycline, compared with 26.9% with placebo (P<0.0001). “Over time, both inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions’ difference to placebo gets wider,” said Dr Kircik.

The most commonly observed treatment-emergent adverse events were nausea, headache, and nasopharyngitis. “For us, it was important to see that sarecycline has only mild gastrointestinal side effects,” said Dr Kircik. Side effects particularly common to tetracyclines—including sunburn, dizziness, photosensitivity, and urticaria—occurred in <1% of sarecycline patients.

10. Bhatia, N. oral presentation session F140, AAD Annual Meeting, February 16–20 2018.

11. Zaenglein, AL. et al J AM Acad Dermatol 2016;74:945–73

12. Thiboutot, D. et al. J AM Acad Dermatol 2018;78:S1–23.

13. Kircik, L. Abstract 6680, AAD Annual Meeting, February 16–20 2018.

Posted on

Previous Article

« New topical and systematic treatments Next Article

New agents and combination therapy »

« New topical and systematic treatments Next Article

New agents and combination therapy »

Table of Contents: AAD 2018

Featured articles

Letter from The Editor

Living in the golden age of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis therapies

Late-breakers

IL-17C inhibition in AD and new oral treatments

Dual JAK/SYK inhibitor and anti-IL-33 blockade

Psoriasis: Selective IL-23 blocker, analysis of VOYAGE-2, dual IL-17 inhibitor and ustekinumab

Hyperhidrosis: Soft molecule and anticholinergic towelettes

Behcet’s syndrome and hidradenitis suppurativa

Psoriasis: an update

Oral therapeutics, supersaturation and excimer laser

Psoriasis management online?

What's hot in atopic dermatitis

AD sleep disturbance, antihistamines and osteoporosis

New topical and systematic treatments

Acne management

Winter effect and preventing scarring

Restrictive antibiotic use and novel tetracycline

Alopecia Areata

Melanoma

Melanoma incidence continues to rise in Europe

Lesions in paediatric patients and possible correlation with coffee drinking

CNNs and targeted combination therapy

Pearls of the posters

Improvement in impact of genital psoriasis on sexual activity with use of ixekizumab

Intralesional cryosurgery and itching in psoriasis

Related Articles

December 20, 2018

Psoriasis management online?

December 21, 2018

Living in the golden age of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis therapies

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com