Reproductive decisions

When people are diagnosed with MS, it comes with a great deal of uncertainty, Prof. D’Hooghe emphasised. “They don’t know what is going to happen. They have to redefine their personal identity and modify their lifestyle (e.g. smoking and diet). Furthermore, they have to consider MS treatment and take into account factors such as way of administration, side effects, complications, and teratogenicity.

Family planning appears to be a major knowledge gap for patients. An online survey in Denmark (n=590) showed that 10% of men and women with MS indicated that there were unplanned pregnancies on DMTs. About half of these pregnancies were terminated and 18% ended in a spontaneous abortion. Only half of the surveyed patients felt well informed about the teratogenic risk of DMTs and family planning. However, 42% female and 74% male patients were not aware of potential teratogenic effects of their current DMTs [1].

MS has a clear impact on reproductive decisions, as there is an increased risk of nulliparity among MS patients, having no children (25.6%) compared with a reference population (19.9%). Furthermore, MS patients have on average fewer children: in females both before and after diagnosis, and in males only after diagnosis [2]. As much as 79% of MS patients indicated that following MS diagnosis there was no pregnancy or fathering pregnancy. It should be noted that this was due to MS-related reasons in only on third of patients; two thirds answered that their family was already complete [3]. The most frequent MS-related reason for not becoming pregnant was the presence of symptoms that might interfere with parenting (71.2%). Other reasons included burdening their partner (50.7%), financial issues (39.4%), worries about children inheriting MS (34.7%), and risks associated with exposure to medication (30%) [3].

Associated disease prognosis

Women of reproductive age have a higher incidence of relapsing-remitting MS, including mild forms (benign MS). They have more relapses, but less disability progression, namely a longer time from onset to EDSS score 6.0 when compared with men. “Women somehow appear to be protected against progression with respect to cognitive impairment, thalamic atrophy, and the occurrence of primary progressive MS during reproductive age”, Prof. D’Hooghe stated. “We really don’t know why this is the case.” There is also no indication that pregnancy has an adverse effect on long-term prognosis of MS, at least according to most studies. “Nevertheless, we know that there is an increased relapse risk in the postpartum period, especially when MS is very active before pregnancy. So, we should be very careful when stopping highly effective DMTs with potential rebound before and during pregnancy.”

Assisted reproductive therapies have also been introduced for MS patients. There appears to be an increased relapse risk following these hormonal treatments, at least when having led to pregnancy. There is no adverse effect of epidural analgesia. MS itself does not appear to have a major effect on reproductive outcomes, i.e. fertility, pregnancy outcomes (abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and delivery), and neonatal outcomes. “We cannot exclude minor effects, but there are no major effects”, Prof. D’Hooghe reassured. “However, DMTs may affect these outcomes due to gonadal/foetal toxicity, birth defects, rebound activity, and autoimmune thyroiditis”, she added, referring to the EMA recommendation about restricted use of fingolimod [4].

Successful pregnancy planning

The trends are that both pregnancy rates and number of annual live births in MS are increasing. However, it appears that women with MS become pregnant with a delay of 2-3 years compared to reference persons, indicating increased risk for the foetus and the mother. Furthermore, there is an increasing number of pregnancies conceived under DMTs. “This is really impressive”, according to Prof. D’Hooghe. “Data from MSBase shows an increase from 26% to 62% with respect to the number of pregnancies conceived under DMTs in recent times.”

Overall, it is important to manage MS with patient preference and reproductive decisions taken into consideration. Before starting, stopping, or switching DMT, it is very relevant to consider the risk of long-term MS disability, to actively ask for pregnancy plans and contraceptive use, to include the mother’s preferences and risk avoidance, and to discuss how contraceptive choice impacts DMT selection. “In case of a pregnancy planning, we should monitor whether disease activity is under control”, Prof. D’Hooghe advised. “We should consider treatment, if needed, with modestly effective DMTs, that are safe to continue taking through to conception. As previously mentioned, that could be injectables rather than orals or second-line therapy. We could also consider not starting with DMT.” Furthermore, Prof. D’Hooghe emphasised the need to restrict the use of highly teratogenic drugs. “These drugs need to be stopped in time, but then there is a risk of relapse. We also have to take into account that there is a variable period to become pregnant (6-24 months). Furthermore, we should restrict the use of highly effective drugs with risk of rebound disease activity 8-16 weeks after cessation, because pregnancy is not protecting against this rebound, so we really have a risk of relapse during pregnancy.”

On the other hand, it is important to avoid unplanned pregnancy under DMT, the motto is: safety first. “During treatment with all DMTs, patients need safe and effective contraception”, D’Hooghe mentioned. “We should be aware that gastrointestinal side effects may reduce effectivity or oral contraceptives. Intrauterine devices may be considered, because they have a long-term effect and are safe. Some highly teratogenic DMTs need double contraceptive method, at least temporarily.”

- Rasmussen PV, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;24:129-134.

- Moberg JY, et al. Mult Scler. 2019:1352458519851245.

- Alwan S, al. Mult Scler. 2013;19:351-8.

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/updated-restrictions-gilenya-multiple-sclerosis-medicine-not-be-used-pregnancy

Posted on

Previous Article

« Transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells Next Article

Influence of age on disease progression »

« Transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells Next Article

Influence of age on disease progression »

Table of Contents: ECTRIMS 2019

Featured articles

Towards a Comprehensive Assessment of MS Course

Cognitive assessment in MS

Late-breaking: Role for CSF markers in autoimmune astrocytopathies

Targeted therapies for NMOSD in development

Monitoring and Treatment of Progressive MS

Challenges in diagnosing and treating progressive MS

Risk factors for conversion to secondary progressive MS

Transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells

Sustained reduction in disability progression with ocrelizumab

Late-breaking: Myelin-peptide coupled red blood cells

Optimising Long-Term Benefit of MS Treatment

Induction therapy over treatment escalation

Treatment escalation over induction therapy

Influence of age on disease progression

Exposure to DMTs reduces disability progression

Predicting long-term sustained disability progression

Treatment response scoring systems to assess long term prognosis

Safety Assessment in the Post-Approval Phase

Use of clinical registries in phase 4 of DMT

Genes, environment, and safety monitoring in using registries

Risk of hypogammaglobulinemia and rituximab

Determinants of outcomes for natalizumab-associated PML

Serum immunoglobulin levels and risk of serious infections

EAN guideline on palliative care

Pregnancy in the Treatment Era

The maternal perspective: when to stop/resume treatment and risks for progression

Foetal/child perspective: risks related to drug exposure and breastfeeding

Patient awareness about family planning represents a major knowledge gap

Late-breaking: Continuation of natalizumab or interruption during pregnancy

Related Articles

December 16, 2020

Novel disease-specific scale confirms huge impact of fatigue

November 25, 2020

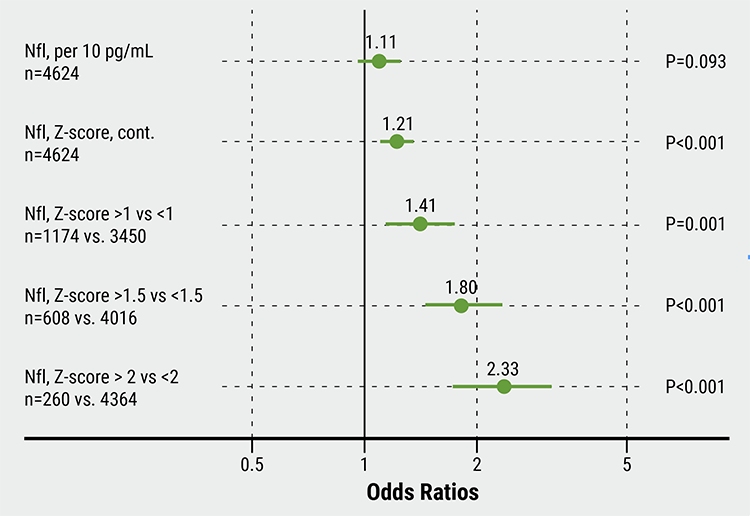

Serum NfL as biomarker for suboptimal treatment response

December 4, 2023

Breakthrough in Predicting MS Progression Through Genetic Testing

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com