https://doi.org/10.55788/d94ba763

After 5 years and with the emergence of abundant valuable evidence, the 2021 ESC Guidelines on HF comprise major changes to those published in 2016. Where overlapping, guidelines were harmonised. The new recommendations, which include a multitude of treatment modifications, have also redefined a phenotype from HF with mid-range EF to HF with mildly reduced EF as a new concept [1]. “After the diagnosis of heart failure is confirmed, the guidelines recommend classification by left ventricular (LV) EF into those with a reduced EF of 40% or less, those with a mildly reduced EF above 40% but less than 50%, and those with a preserved EF of 50% or more” explained Prof. Carolyn Lam (Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore) [2]. She added, “importantly for all forms, the presence of a clinical syndrome of HF is a prerequisite.” The rationale behind this new category is that patients with mildly reduced EF could benefit from treatment with medications indicated for those with reduced EF (HFrEF). This is reflected in a ‘may be considered’ class 2b recommendation for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), β-blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan [1,2]. More details and practical guidance for the clinical practice are provided in the online supplementary material published with the guidelines [1].

Management before and after hospital discharge

The importance of optimal HF treatment before leaving the hospital accompanied by subsequent out-patient management shortly afterwards has also been acknowledged with 3 new class-1 recommendations:

- it is recommended that patients hospitalised for HF should be carefully evaluated to exclude persistent signs of congestion before discharge and to optimise oral treatment;

- it is recommended that evidence-based oral medical treatment should be administered before discharge; and

- an early follow-up visit is recommended at 1–2 weeks after discharge to assess signs of congestion, drug tolerance, and start and/or up-titrate evidence-based therapy [1].

Patients with HFrEF

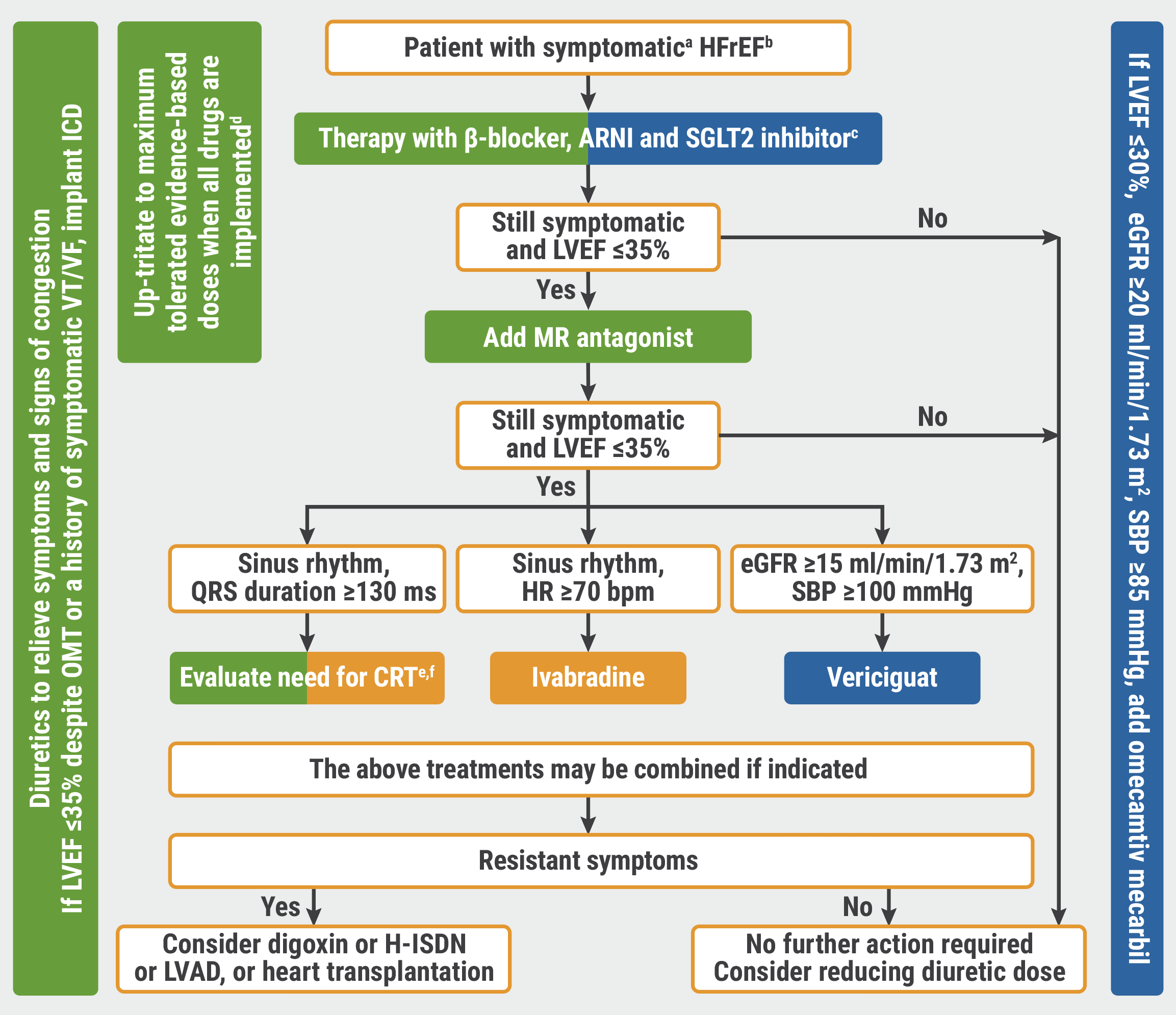

The medication for HFrEF is now based on a triplet of ACEI/ARNI, β-blockers, and MRA that should be up-titrated to clinical trial dosages or as tolerated if no contraindication is present (see Figure) [1,3].

Furthermore, with the introduction of SGLT2 inhibitors, a new class of drugs has been added in a general class-1 recommendation after clear evidence in clinical trials:

- Dapagliflozin or empagliflozin are recommended for patients with HFrEF to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation and death.

Additionally, in a special population with HFrEF, vericiguat received a new class-2b recommendation:

- Vericiguat may be considered in patients in NYHA class II–IV who have had worsening HF despite treatment with an ACEI (or ARNI), a β-blocker and an MRA to reduce the risk of CV mortality or HF hospitalisation.

In 2021, ESC is calling for a change in treatment that moves away from lengthy sequential approaches of care to on-time strategies that focus on keeping people out of the hospital and from experiencing complications from HFrEF, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD). Considering that roughly 40% of patients with HF also have CKD or diabetes, the recommendation to apply the new first-line treatments underscores the importance of managing multiple risks, addressing the underlying pathophysiology of cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal diseases.

Early initiation in the shortest time possible with the 4 key drug therapies ACE-I, β-blockers, MRAs and ARNI (sacubitril/valsartan, class 2b) and personalising the approach based on comorbidities at the first-line is a significant step forward. Diuretics can be applied based on volume load. All HF patients with type 2 diabetes should be treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor; the choice between empagliflozin or dapagliflozin (both class 1a) is up to the attending physician.

Figure: Treatment algorithm for patients with HFrEF [4] aNYHA class II-IV; bLVEF <40%, cβ-blocker is recommended; dif not contraindicated; eCRT is recommended if QRS ≥130 ms and LBBB (in sinus rhythm); fCRT should/may be considered if QRS ≥130 ms with non-LBBB (in a sinus rhythm) or for patients in AF provided a strategy to ensure bi-ventricular pacing.

aNYHA class II-IV; bLVEF <40%, cβ-blocker is recommended; dif not contraindicated; eCRT is recommended if QRS ≥130 ms and LBBB (in sinus rhythm); fCRT should/may be considered if QRS ≥130 ms with non-LBBB (in a sinus rhythm) or for patients in AF provided a strategy to ensure bi-ventricular pacing.

AF, atrial fibrillation; ARNI, angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitor; bpm, beats per minute; CRT, cardiac resynchronisation therapy; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; H-ISDN, hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate; HR, heart rate; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVAD, left ventricle assist device; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OMT, optimal medical therapy; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SGLT2 sodium-glucose co-transporter-2; VT/VF, ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation.

Comorbidities in heart failure

Important changes have been incorporated for the treatment of several cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular diseases found in HF patients with chronic coronary syndrome:

- in patients suitable for surgery, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) should be considered as the first-choice revascularisation strategy, especially if they have diabetes and for those with multivessel disease (class 2a);

- in LV assist device candidates needing coronary revascularisation, CABG should be avoided if possible (class 2a);

- coronary revascularisation may be considered to improve outcomes in patients with HFrEF, chronic coronary syndrome, and coronary anatomy suitable for revascularisation, after careful evaluation of the individual risk-benefit ratio, including coronary anatomy, comorbidities, life expectancy, and patient’s perspectives (class 2b); and

- PCI may be considered as an alternative to CABG, based on Heart Team evaluation, considering coronary anatomy, comorbidities, and surgical risk (class 2b) [1,5].

In patients who have diabetes as well as HF, recommendations also concern the inclusion of SGLT2 inhibition:

- SGLT2 inhibitors (i.e. canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, ertugliflozin, and sotagliflozin) are recommended in patients with type 2 diabetes at risk of CV events to reduce hospitalisations for HF, major CV events, end-stage renal dysfunction, and CV death (class 1); and

- SGLT2 inhibitors (i.e. dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, and sotagliflozin) are recommended in patients with type 2 diabetes and HFrEF to reduce hospitalisations for HF and CV death.

Furthermore, screening and treating iron deficiency merited new recommendations:

- it is recommended that all patients with HF are periodically screened for anaemia and iron deficiency with a complete blood count, serum ferritin concentration, and transferrin saturation; and

- intravenous iron supplementation with ferric carboxymaltose should be considered in symptomatic HF patients recently hospitalised for HF and with LVEF ≤50% and iron deficiency, defined as serum ferritin <100 ng/mL or serum ferritin 100–299 ng/mL with transferrin saturation <20% to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation.

Since clinical trials have also revealed the possibility that an efficacious treatment for amyloidosis might lead to heart failure, 2 new class 1-recommendations have been added for this patient population:

- tafamidis is recommended in patients with genetic testing proven hereditary transthyretin-cardiomyopathy and NYHA class I or II symptoms to reduce symptoms, CV hospitalisation and mortality; and

- tafamidis is recommended in patients with wild-type transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis and NYHA class I or II symptoms to reduce symptoms, CV hospitalisation, and mortality.

In addition, a new class-1 recommendation has been introduced recommending heart transplant consideration for patients with advanced HF who are refractory to medical/device therapy and who do not have absolute contraindications [1,6].

As a final remark on the 2021 Heart Failure Guidelines, guideline co-author Prof. Marco Metra (University of Brescia, Italy) called his fellow cardiologists to action: “now, we have new evidence, we have new guidelines from the ESC, and it’s our task to implement them in our clinical practice” [7].

- McDonagh TA, et al. Eur Heart J 2021;42(36):3599–3726.

- Lam CS. Classification of HF and diagnosis and treatment of HFmrEF and HFpEF. Session: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure, ESC Congress 2021, 27–30 August.

- Gardner RS. New recommendations for the treatment of HFrEF. Session: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure, ESC Congress 2021, 27–30 August.

- Dębska-Kozłowska A, et al. Heart Fail Rev 2021;May 29. DOI:10.1007/s10741-021-10120-x.

- Adamo M. New recommendations for comorbidities. Session: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure, ESC Congress 2021, 27–30 August.

- Chioncel O. Advanced and acute heart failure. Session: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure, ESC Congress 2021, 27–30 August.

- ESC TV at #ESCCongress 2021 – 2021 ESC Guidelines on Heart Failure.

Copyright ©2021 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

« 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Valvular Heart Disease Next Article

Antagonising the mineralocorticoid receptor beneficial for patients with diabetes and CKD »

Table of Contents: ESC 2021

Featured articles

2021 ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines

2021 ESC Guidelines on Heart Failure

2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on Valvular Heart Disease

2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiac Pacing and Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy

2021 ESC Guidelines on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Best of the Hotline Sessions

Empagliflozin: First drug with clear benefit in HFpEF patients

CardioMEMS: neutral outcome but possible benefit prior to COVID-19

Cardiac arrest without ST-elevation: instant angiogram does not improve mortality

Older hypertensive patients benefit from intensive blood pressure control

Antagonising the mineralocorticoid receptor beneficial for patients with diabetes and CKD

Late-Breaking Science in Heart Failure

Valsartan seems to attenuate hypertrophic cardiomyopathy progression

Dapagliflozin reduces incidence of sudden death in HFrEF patients

Late-Breaking Science in Hypertension

Smartphone app improves BP control independent of age, sex, and BMI

QUARTET demonstrates that simplicity is key in BP control

Salt substitutes: a successful strategy to improve blood pressure

Late-Breaking Science in Prevention

NATURE-PCSK9: Vaccine-like strategy successful in lowering CV events

Polypill: A successful tool in primary prevention

Important Results in Special Populations

VOYAGER PAD: Fragile or diabetic patients also benefit from rivaroxaban

COVID-19 and the Heart

Rivaroxaban improves clinical outcomes in discharged COVID-19 patients

COVID-19: Thromboembolic risk reduction with therapeutic heparin dosing

Long COVID symptoms – Is ongoing cardiac damage the culprit?

ESC Spotlight of the Year 2021: Sudden Cardiac Death

Breathing problems: the most frequently reported symptom before cardiac arrest

Lay responders can improve survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

Related Articles

Letter from the Editor

Long COVID symptoms – Is ongoing cardiac damage the culprit?

Empagliflozin: First drug with clear benefit in HFpEF patients

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com