Steadily increasing recognition is being awarded to the fact that -like psoriasis of the skin- PsA can be multifaceted; however, unlike rheumatoid arthritis, PsA can affect tissues beyond the joints [2]. For example, Prof. Boehncke detailed, inflammation in PsA can result in swelling of an entire toe, especially associated tendons and their entheses (attachments to bone). There is an enormous benefit in coupling the knowledge from the rheumatology and dermatology fields in understanding and treating PsA. The pathogenesis of PsA shares many components of psoriasis pathogenesis known to dermatologists (e.g. tumour necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-alpha], IL-17, and IL-23), whereas rheumatologists have a few advantages when it comes to treating systemic disease with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.

In addition to the anti-IL-17 drugs used in psoriasis, rheumatologists treat PsA with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which dermatologists of course would not use for the skin, as well as methotrexate and other drugs like leflunomide and sulfasalazine, they have access to 2 anti-TNF-alpha drugs which are not approved for psoriasis but only for psoriatic arthritis, as well as the PDE-4 inhibitor apremilast. The treatment decision landscape for PsA is complex and requires an algorithm taking 6 different domains into account to scope the current pharmacological therapies for PsA [3]. At the risk of oversimplifying this algorithm, Prof. Boehncke pointed out that TNF-alpha blockade seems to be the gold standard for treating PsA in the rheumatology world, yet so much new evidence has come out since the 2016 algorithm and the 2017 Ritchlin review in New England Journal of Medicine [2,3]. One important trend Prof. Boehncke explained is the use of minimal disease activity as a relevant endpoint for PsA, and this is a novel concept for dermatologists. The pivotal study was a 2018 trial of guselkumab -a selective IL-23 inhibitor targeting the p19 subunit- in PsA patients using minimal disease activity as the endpoint [4].

One exciting paper provided proof-of-concept about combined inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F by bimekizumab [5]. The rationale for neutralising IL-17F together with IL-17A is that IL-17A and IL-17F are expressed at sites of inflammation and independently cooperate with other cytokines to mediate inflammation in humans. The clinical hypothesis is that neutralising IL-17F in addition to IL-17A will result in an improved complementary suppression of inflammation compared with inhibition of IL-17A alone. In addition to proving clinical efficacy of dual inhibition, the authors demonstrated on a molecular level that IL-17A works synergistically with IL-17F. They exposed synoviocytes to supernatants of Th17 cells and then tried to block the production of IL-17A, using recruitment of neutrophils as an in vitro readout. Then they did a deeper gene expression analysis, elegantly demonstrating that dual inhibition of IL-17A together with IL-17F normalised the expression of a number of genes that are relevant for joint inflammation. Prof. Boehncke said during his presentation: “This paper shows us that the IL-17 story is much more complicated that we previously thought […] it is not just IL-17A, it’s F, it’s E, it’s C, and it’s not just Th17 helper cells anymore, it’s other cells as well.”

Inhibition of Janus kinase (JAK) for treatment of PsA has been discussed often this year; tofacitinib showed promising data at two doses, and performed as well as adalimumab vs placebo in psoriatic arthritis, demonstrating that tofacitinib is a fairly good drug for PsA [6]. Tofacitinib was also in the dermatology arena for a while, but the company has decided against pursuing tofacitinib for psoriasis, despite being approved, due to reported toxicities.

So, is TNF-alpha inhibition still the best treatment for PsA? The ECLIPSA trial challenges this dogma [7]. Prof. Boehncke pointed out: “One bias becomes really evident when you reassess the trials performed [...] no one uses the psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score to measure atopic eczema, yet researchers use the ACR arthritis criteria to score PsA severity, for which there is absolutely no validation.” Prof. Georg Schett (University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany) and colleagues performed a single-centre retrospective study comparing ustekinumab with all the TNF-alpha inhibitors in PsA patients. The results, albeit not of the highest level of evidence, were astounding: while ustekinumab worked better on the skin as anticipated, no significant differences were observed with regard to tender and swollen tendons seen in psoriatic and rheumatic arthritis, but the data regarding enthesitis unequivocally demonstrated ustekinumab outperforming the TNF-alpha inhibitors. To understand this result, we should critically evaluate whether the ACR criteria perform well in PsA patients. Rheumatoid arthritis does not exhibit dactylitis, enthesitis, or nail involvement, and ACR does take these PsA-associated pathologies into account. Thus, one cannot use the old datasets demonstrating better outcomes for anti-TNF therapies because they always used ACR and therefore did not consider patient-relevant outcomes in patients with PsA. Developing a severity index and outcome measures appropriate and validated for PsA is essential, and once the data is disease-specific, it may well be that the anti-TNF dogma falls.

One well-known concept in many specialties including rheumatology, but still relatively unknown to dermatology, is the objective to treat-to-target (T2T). The primary outcome of the T2T concept is minimal disease activity. The definition of minimal disease activity in PsA trials has been repeatedly validated in numerous trials [8,9]: TJC ≤1; SJC ≤1; PASI ≤1; VAS pain ≤15mm; VAS Pat. Global Disease Activity ≤20 mm; HAZ ≤0.5; ≤1 painful enthesial site. The Coates group in Leeds (UK) put T2T to the test by asking whether using minimal disease activity as the treatment goal would improve hard patient outcomes like ACR and PASI. The TICOPA trial randomised patients into either standard care (office assessment every 2-3 months) or into a T2T arm where patients were assessed regularly every 4 weeks, and if the patient had not reached the treatment goal, the treatment was intensified. At the end of 1 year, all the outcomes including the ACR 20-50-70 and the PASI score were significantly better among the people in the T2T arm vs the standard of care arm [10]. The take-home message from this study is that using minimal disease activity is a flexible and aggressively worthwhile approach to control disease progression in early PsA patients.

A coordinated effort of Canadian rheumatologists and dermatologists looking at psoriatic disease generated a consensus statement concerning the application of the T2T concept for daily practice [11]. The summary of their T2T recommendations is as follows:

- Clear or almost clear skin should be the target for psoriasis regardless of the area affected or duration of disease.

- A state of minimal disease activity is a therapeutic target for psoriatic arthritis.

- Quality of life is an important outcome and should always be a therapeutic target.

- Functional impairment, comorbidities, and treatment risks should be considered in addition to assessing measure of disease activity.

- Physicians and patients must agree on the selected therapeutic targets.

- Patients must be treated adequately to reach the selected therapeutic targets, with therapy adjustments every 3 months for patients with active disease and every 6-12 months for static disease after therapeutic targets are reached.

- The state of clear or almost clear skin should be maintained for as long as possible with adjustment in therapy at the first signs of disease progression.

- Standard safety assessments should be performed at each visit.

In conclusion, numerous novel mediators of inflammation in PsA have been identified in the last few years and the field is changing rapidly. More importantly, some of these mediators have successfully been used as targets for innovative therapies, e.g. blocking IL-17F in addition to IL-17A, or the anti-IL-23 class of drugs. Assessment of individual PsA disease may be improved by replacing ACR criteria (which were not made with PsA in mind) with PsA-focussed measures, which may lead to the revision of current treatment algorithms and will likely challenging the dogma that TNF inhibitors are the superior drugs for PsA treatment. Dermatologists need to come to a joint decision-making era with rheumatologist in PsA treatment, and dermatologists need to share their experience with the innovative biologics, which are more effective than TNF-alpha blockade for psoriasis management. Rheumatologists may be hesitant to pursue these treatment options because ACR criteria are the only data collected so far. Lastly, T2T is about to become a widely established therapeutic strategy in other specialties and has been proven effective in PsA patients as well. Prof. Boehncke concludes: “It is time for dermatologists to jump on this fast-moving train!”

- Boehncke WH. O017, SPIN 2019, 25-27 April, Paris, France.

- Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. N Engl J Med. 2017 Mar 9;376(10):957-970.

- Coates LC, et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 May;68(5):1060-71.

- Deodhar A, et al. Lancet. 2018 Jun 2;391(10136):2213-2224.

- Glatt S, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018 Apr;77(4):523-532.

- Mease P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1537-1550.

- Araujo et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019 Feb;48(4):632-637.

- Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 Jul;62(7):965-9.

- Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010 Sep;49(9):1793-4; author reply 1794.

- Coates LC, et al. Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386(10012):2489-98.

- Gladman DD, et al. J Rheumatol. 2017 Apr;44(4):519-534.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Favourable safety profile of long-term use of ixekizumab Next Article

How can societies help to implement personalised treatment? »

« Favourable safety profile of long-term use of ixekizumab Next Article

How can societies help to implement personalised treatment? »

Table of Contents: SPIN 2019

Featured articles

Letter from the Editor

Aetiology: Triggers and Risk Factors

Understanding genetics to unravel psoriasis and atopic dermatitis pathogenesis

Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis: on a spectrum?

Advances in Therapy

Advances in target-oriented therapy: psoriatic arthritis

Favourable safety profile of long-term use of ixekizumab

Brodalumab onset of action is significantly faster than ustekinumab: Results from the phase 3 AMAGINE-2 and -3 studies

Adalimumab vs adalimumab + methotrexate in psoriasis: First-year results on effectiveness, drug survival, safety, and immunogenicity

Ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in paediatric patients

Fumarates and vitamin A derivatives advance and latest insights in non-biologic systemic therapeutic agents in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis

Certolizumab: Long-term safety and efficacy results for psoriasis-related nail disease

Novel Considerations

Granulomatous rosacea: exploratory histological markers

Live imaging of cutaneous immune responses

Results from the ECLIPSE trial: does blocking IL-23 have better long-term outcomes in psoriasis?

ABP501 biosimilar for adalimumab: What you need to know

Sustained and complete responses from the phase 3 AMAGINE-2 and -3 studies

Reduction in coronary artery disease in psoriasis patients treated with biologic therapies, possible implications for atopic dermatitis

Small molecules, apremilast, and TYK2

Related Articles

November 4, 2020

Gut microbe curbs systemic inflammation in psoriasis

August 26, 2019

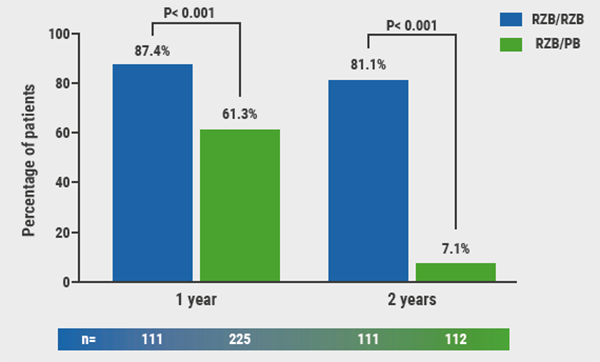

Novel selective IL-23 blocker highly effective over 2 years

September 17, 2021

Low COVID-19 risk for patients with psoriasis on biologic treatment

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy