Factors that need to be taken into account are gender, year of DMT start, type of DMT, pre-DMT relapses, EDSS, time since first MS symptom, and MS severity score [4]. Dr Viktor von Wyl (University of Zurich, Switzerland) tried to answer this question using the Swiss Association for Common Tasks of Health Insurers database which contains data from 14,718 MS patients who initiated their first DMT between 1995 and 2017 (69% women; 85% relapsing-remitting MS; mean age 39±11.5 years; disease duration 6±8 years; 80% IFN-beta or glatiramer acetate) [5].

Data from 9,705 MS patients were eligible for this analysis. The association between age at disease onset and EDSS progression had a sigmoidal shape: EDSS progression hazard remained stable in patients with disease onset from early childhood to about 32 years; then increased sharply around the age of 45 years; and afterwards remained stable at a relatively high level [6]. In contrast, the association between age at disease onset and relapse risk was almost linear: the risk for relapse was highest at younger ages and decreased continuously from childhood to around 35 years of age. For example, a 20-year old patient with first symptoms of MS had a 1.5-fold higher risk for relapse on DMT than a 38-year old patient, after adjustment for other factors (gender, relapse-activity before DMT initiation, EDSS, pyramidal functional system score, and MS severity score). Risk of relapse remained constant for a decade and then continuously decreased from age 45 years onwards.

So, age at DMT start is an important factor affecting relapse and confirmed disability progression, independent of other characteristics and possibly type of DMT. Age at first symptom onset and disease duration are also relevant and correlated with age at DMT start. The age between 37 and 40 years seems critical with regard to the compensation of damage in the central nervous system caused by MS. Patients older than 40 years who start with a DMT have a higher risk of disability progression, when controlling for important clinical disease characteristics [6].

- Renoux C, et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2603-13.

- Benson LA, et al. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:186-93.

- Gorman MP, et al. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:54-9.

- Roxburgh RH, et al. Neurology. 2005;64:1144-51.

- Lorscheider J, et al. Mult Scler. 2018;24:777-785.

- von Wyl V, et al. ECTRIMS 2019, abstract 302.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Patient awareness about family planning represents a major knowledge gap Next Article

pTMB is a feasible predictive biomarker for chemoimmunotherapy »

« Patient awareness about family planning represents a major knowledge gap Next Article

pTMB is a feasible predictive biomarker for chemoimmunotherapy »

Table of Contents: ECTRIMS 2019

Featured articles

Towards a Comprehensive Assessment of MS Course

Cognitive assessment in MS

Late-breaking: Role for CSF markers in autoimmune astrocytopathies

Targeted therapies for NMOSD in development

Monitoring and Treatment of Progressive MS

Challenges in diagnosing and treating progressive MS

Risk factors for conversion to secondary progressive MS

Transplantation of autologous mesenchymal stem cells

Sustained reduction in disability progression with ocrelizumab

Late-breaking: Myelin-peptide coupled red blood cells

Optimising Long-Term Benefit of MS Treatment

Induction therapy over treatment escalation

Treatment escalation over induction therapy

Influence of age on disease progression

Exposure to DMTs reduces disability progression

Predicting long-term sustained disability progression

Treatment response scoring systems to assess long term prognosis

Safety Assessment in the Post-Approval Phase

Use of clinical registries in phase 4 of DMT

Genes, environment, and safety monitoring in using registries

Risk of hypogammaglobulinemia and rituximab

Determinants of outcomes for natalizumab-associated PML

Serum immunoglobulin levels and risk of serious infections

EAN guideline on palliative care

Pregnancy in the Treatment Era

The maternal perspective: when to stop/resume treatment and risks for progression

Foetal/child perspective: risks related to drug exposure and breastfeeding

Patient awareness about family planning represents a major knowledge gap

Late-breaking: Continuation of natalizumab or interruption during pregnancy

Related Articles

September 7, 2023

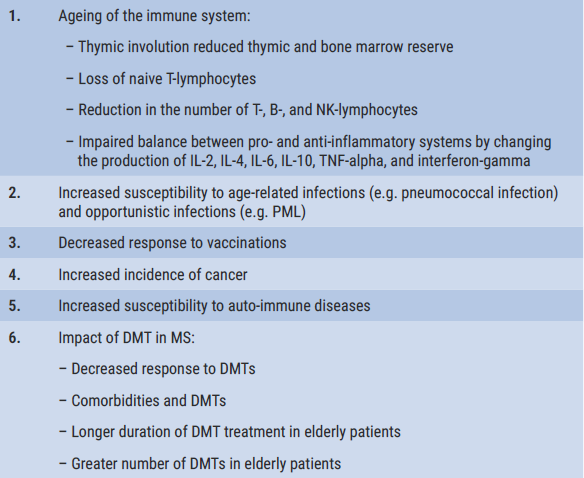

Immunosenescence and MS: relevance to immunopathogenesis and treatment

November 25, 2020

Safety and efficacy of cladribine, glatiramer acetate, and more

September 10, 2020

Switching from natalizumab to moderate- versus high-efficacy DMT

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com