https://doi.org/10.55788/fb31e0b8

Prof. Elena Arbelo (University of Barcelona, Spain) pointed out that this is a new guideline, not an update of an existing guideline, which covers all subtypes of cardiomyopathies (CMs) [1]. The only exception is the section on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which was a focused update of the 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of HCM [2]. The novel guideline contains 158 recommendations, almost half of which are class I. Unfortunately, the evidence for this guideline is based on retrospective data in 65% of cases, due to the rarity of the disease.

In general, CM is defined as a myocardial disorder in which the heart muscle is structurally and functionally abnormal, in the absence of coronary artery disease, hypertension, valvular disease, and congenital heart disease sufficient to cause the observed myocardial abnormality.

Phenotypic approach to cardiomyopathies

A key aspect of the novel guideline is the phenotypic approach and the systematic characterisation of these CMs. “We have to look for morphological and functional traits,” Prof. Arbelo explained. Particularly, it is important to identify non-ischaemic ventricular scars and other myocardial tissue characterisation features on cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR). “With that, we will be able to establish 5 different CM phenotypes:”

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM);

- dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM);

- non-dilated left ventricular cardiomyopathy (NDLVC);

- arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC); and

- restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM).

There are specific conditions that were formerly considered to be external causes of CM and were recently proved to have genetic contributors. Examples are:

- titin gene truncating variants (TTNtv) represent a prevalent genetic predisposition for alcoholic CM;

- TTNtv also appear to be associated with an increased risk of cancer therapy-induced CM; and

- rare truncating variants in 8 genes are found in 15% of women with peripartum CM.

In the new guideline, the multidisciplinary care of patients with CM is emphasised. A shared and coordinated approach between CM specialists and general adult and paediatric cardiology centres is strongly recommended (class I recommendation, level C).

There are also recommendations regarding the diagnostic workflow of CM. All patients with suspected or established CM should undergo systematic evaluation using a multiparametric approach that includes clinical evaluation, pedigree analysis, ECG, Holter monitoring, laboratory tests, and multimodality imaging.

Moreover, all patients with suspected CM should undergo evaluation for family history and a 3–4-generation family tree should be created to aid in diagnosis, provide clues to underlying aetiology, determine inheritance patterns, and identify at-risk relatives.

Contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance in every patient

“I want to emphasise the importance of CMR, not only for the diagnosis of CM, but also to allow monitoring of disease progression and risk stratification and management,” said Prof. Arbelo. Therefore, contrast-enhanced CMR is recommended in every patient with signs of CM at the initial evaluation. Certain examples of CMR imaging tissue characterisation can raise the suspicion of specific aetiologies, as shown for HCM (see Table). Moreover, in families with CM in which a disease-causing variant has been identified, contrast-enhanced CMR should be considered in genotype-positive/phenotype-negative family members, to aid diagnosis and detection of early disease.

Table: CMR imaging tissue characterisation hints at specific diseases that have to be considered. Modified from [3]

HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy.

The genetic section is an important new addition to the guideline. Genetic testing should be offered to all patients fulfilling diagnostic criteria for CM. If a confident genetic diagnosis has been established in an individual with CM in the family, cascade genetic testing with pre- and post-test counselling is recommended for adult at-risk relatives (class I) and paediatric at-risk relatives (class IIa). In addition, clinical psychological support should be offered to all patients who have undergone implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) implantation or who have a family history of sudden cardiac death (SCD).

From the description of phenotype to an aetiology-driven management

Dr Juan Pablo Kaski (University College London, UK) pointed out that a key element of the guideline is the concept of the diagnostic workflow, which starts with a detailed description of the phenotype but leads towards an aetiology-driven management.

Most recommendations regarding HCM, being the most frequent CM with a prevalence of 0.2% in adults, did not change. However, there is a new treatment recommendation regarding the management of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO): the cardiac myosin ATPase inhibitor mavacamten, a first-in-class drug, is recommended as second-line treatment (class IIa) for patients who are still symptomatic after therapy with beta-blockers, verapamil, or diltiazem.

“Sudden death risk prevention in CMs, in particular in primary prevention, is a major aspect of the management of CM,” Dr Kaski said. Therefore, there are additional recommendations for the prevention of SCD in patients with HCM. For example, a broader indication for prophylactic ICD implantation is given for patients who are in the low-risk category (<4% estimated 5-year risk of SCD). Shared decision-making with the patient is advised in these cases.

Genotype: of key importance for prediction of sudden cardiac death

According to a new recommendation, the patient’s genotype should be considered in the estimation of SCD risk in DCM. A new table depicts high-risk genotypes and associated predictors of SCD. Many subtypes are inherited in an autosomal dominant way. When such a mutation is found, testing of relatives can be considered.

Finally, there are recommendations favouring regular low- or moderate-intensity exercise in all able individuals with CM. An individualised risk assessment should be performed so that an exercise prescription can be provided, bearing in mind the prevention of life-threatening arrhythmias during exercise.

- Arbelo E, et al. Eur Heart J. 2023 2023 Aug 25. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad194.

- Elliott PM, et al. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733–2779.

- Presentations in session: ‘2022 ESC Guidelines Overview,’ ESC Congress 2023, 25–28 August, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Copyright ©2023 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF Next Article

Can aspirin be omitted after PCI in patients with high bleeding risk? »

« DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF Next Article

Can aspirin be omitted after PCI in patients with high bleeding risk? »

Table of Contents: ESC 2023

Featured articles

How to manage arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19?

2023 ESC Guidelines & Updates

Heart failure: the 2023 update

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies

Cardiovascular disease and diabetes: new guidelines

Guidelines for the management of endocarditis

Trial Updates in Heart Failure

Traditional Chinese medicine successful in HFrEF

CRT upgrade benefits patients with HFrEF and an ICD

Catheter ablation saves lives in end-stage HF with AF

Meta-analysis: Does FCM improve clinical outcomes in HF?

HEART-FID: Is intravenous ferric carboxymaltose helpful in HFrEF with iron deficiency?

Natriuresis-guided diuretic therapy to facilitate decongestion in acute HF

DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF

STEP-HFpEF: Semaglutide safe and efficacious in HFpEF plus obesity

Key Research on Prevention

Does colchicine prevent perioperative AF and MINS?

Diagnostic tool doubles cardiovascular diagnoses in patients with COPD or diabetes

Inorganic nitrate strongly reduces CIN in high-risk patients undergoing angiography

Finetuning Antiplatelet and Anticoagulation Therapy

Should we use anticoagulation in AHRE to prevent stroke?

Results of FRAIL-AF trial suggest increased bleeding risk with DOACs

The optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy in cancer patients with DVT

DAPT or clopidogrel monotherapy after stenting in high-risk East-Asian patients?

Assets for ACS and PCI Optimisation

Immediate or staged revascularisation in STEMI plus multivessel disease?

Lp(a) and cardiovascular events: which test is the best?

No benefit of extracorporeal life support in MI plus cardiogenic shock

Functional revascularisation outperforms culprit-only strategy in older MI patients

Can aspirin be omitted after PCI in patients with high bleeding risk?

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis

OCTOBER trial: OCT-guided PCI improves clinical outcomes in bifurcation lesions

Other

Minimising atrial pacing does not reduce the risk for AF in sinus node disease

ARAMIS: Can anakinra alleviate acute myocarditis?

Expedited transfer to a specialised centre does not improve cardiac arrest outcomes

Acoramidis improves survival and functional status in ATTR-CM

Related Articles

October 30, 2023

DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF

October 30, 2023

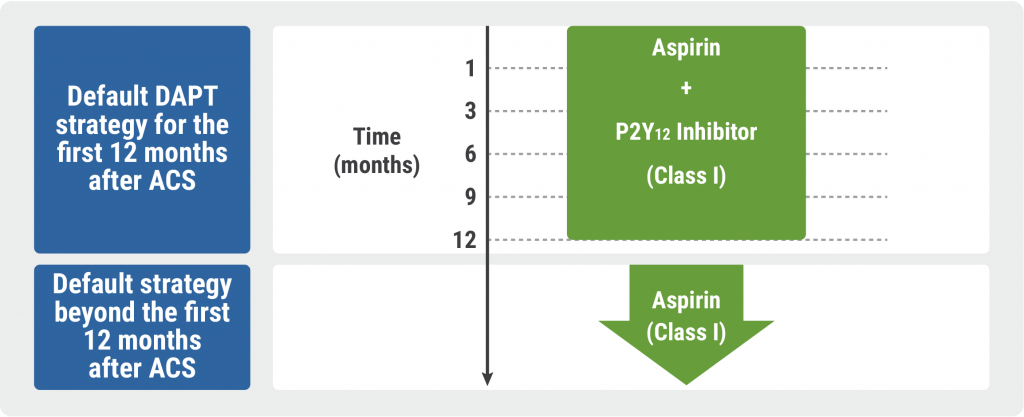

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

October 30, 2023

Results of FRAIL-AF trial suggest increased bleeding risk with DOACs

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com