Medicom interviews Prof. Bonaca to gain some insight into the following drugs selected to undergo negotiations:

Medicom interviews Prof. Bonaca to gain some insight into the following drugs selected to undergo negotiations:- Apixaban (Eliquis), an oral anticoagulant

- Rivaroxaban (Xarelto), an oral anticoagulant

- Sitagliptin (Januvia), a diabetes drug

- Empagliflozin (Jardiance), a diabetes drug

- Etanercept (Enbrel), a rheumatoid arthritis drug

- Ibrutinib (Imbruvica), a drug for blood cancers

- Dapagliflozin (Farxiga), a drug for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease

- Sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto), a heart failure drug

- Ustekinumab (Stelara), a drug for psoriasis and Crohn's disease

- Insulin aspart (Fiasp and NovoLog), for diabetes

Together, the 10 drugs selected account for $50.5 billion, or 20%, of Medicare Part D spending in the last year.

Medicare recently released a list of 10 drugs for which they have negotiated prices. In Europe, we are accustomed to this negotiation process, but this is the first time the US has negotiated prices on multiple drugs. The list includes several drugs that you commonly prescribe. Could you comment on the selection of these drugs and why you believe negotiating their prices is crucial?

“Yes, the first 10 drugs identified for price negotiations by Medicare include apixaban, empagliflozin, rivaroxaban, sitagliptin, dapagliflozin, and sacubitril/valsartan. These are all cardiovascular and cardiometabolic drugs that have demonstrated significant benefits for patients with these conditions in recent studies. We frequently use these medications in our practice.In general, these drugs are underutilised compared with their potential impact based on real-world data. For instance, a significant portion of patients with atrial fibrillation remain un-anticoagulated despite their indication for apixaban or rivaroxaban. Similarly, dapagliflozin for heart failure is not prescribed as often as it should be.

The reasons for this underutilisation are multifaceted, but cost may be a contributing factor. Additionally, access to these medications can be challenging. Therefore, this price negotiation initiative is particularly important for cardiovascular and cardiometabolic practitioners in the United States.”

Do you believe this will be a game-changer? Will this provide access to populations that may be underrepresented in clinical trials?

“Yes, I believe this has the potential to be a game-changer. Increasing access in a complex market like the US is undoubtedly beneficial. However, the extent to which cost contributes to underutilisation is debatable.

Implementation science programs have demonstrated that we can often obtain these drugs for patients when we fully understand the various payment support programs and other available options. The challenge lies in navigating this complex system, which healthcare systems are not particularly adept at. Therefore, I'm not certain whether this will improve access. However, it should certainly reduce the cost burden for payers.”

Could this broader application also lead to unintended consequences?

“I am particularly concerned about the potential unintended consequences of this blunt tool approach, particularly on research and development. Pharmaceutical companies have raised concerns about the impact on their extensive research and development efforts.

These companies make significant investments to discover efficacious and safe drugs and provide the necessary evidence base. Take rivaroxaban for example. The cardiovascular development program for rivaroxaban is the largest of its kind for any drug ever developed. This extensive research has provided valuable insights that inform future research.

Quantifying the benefit of these research efforts is challenging. Companies can still conduct phase 3 trials and obtain approval, but for clinicians, the availability of multiple trials across various disease states and populations is crucial for guiding the application of drug classes.

I am concerned that this price negotiation approach could have adverse consequences on the funding of implementation science, which seeks to understand the reasons behind drug underutilisation. This field has been underfunded in the past, and I fear that emphasis on cost reduction as the primary solution could further hinder our understanding of the complex factors contributing to underutilisation.”

You mentioned the importance of capturing data and assessing the impact of these drugs on our patients. How can we, as practising physicians, best accomplish this?

“Randomised clinical trials remain the gold standard for understanding the true effects of a drug. These trials are large-scale and expensive, but they provide the most reliable evidence. Real-world data analysis also plays a significant role in understanding real-world risks, uptake, utilisation, and subgroup effects that may not have been captured in clinical trials. Both methods are important.As clinicians, we should actively participate in research. In oncology, for instance, nearly every patient is offered the opportunity to participate in a trial. This should be the standard in cardiovascular medicine as well. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death, yet participation rates in clinical trials are low.

Instead of focusing solely on drug cost reduction, we should strive to make research more efficient. How can we reduce the cost of research and make it accessible to every patient at risk of or with cardiovascular disease? Can we leverage pragmatic trials more effectively? Can we learn more efficiently by reducing costs?

Addressing these questions could ultimately lead to lower drug costs if the investment in evaluating their efficacy and safety is less expensive. This is an area where our non-profit research group is deeply committed, and it's a very different situation than large, randomised trials. We have to personalise. We have to engage in shared decision-making. Cost is always one of those factors, but we know there's much more than that. I think that this sort of noise can't interrupt that sacred patient-doctor or patient-provider shared decision-making relationship.

We have to remember to do what's right for our patients and prescribe the right drugs or not, depending on what we think is best. But I think we also need to wear the hat of advocates for our patients and to advocate for access to the most important therapies and for a system that continues to drive new developments that will improve outcomes for our patients. "

Copyright ©2024 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« Interview: Sandwich treatment model shows promise for mantle cell lymphoma Next Article

Pregnancy is not contraindicated in pathogenic BRCA carriers »

« Interview: Sandwich treatment model shows promise for mantle cell lymphoma Next Article

Pregnancy is not contraindicated in pathogenic BRCA carriers »

Related Articles

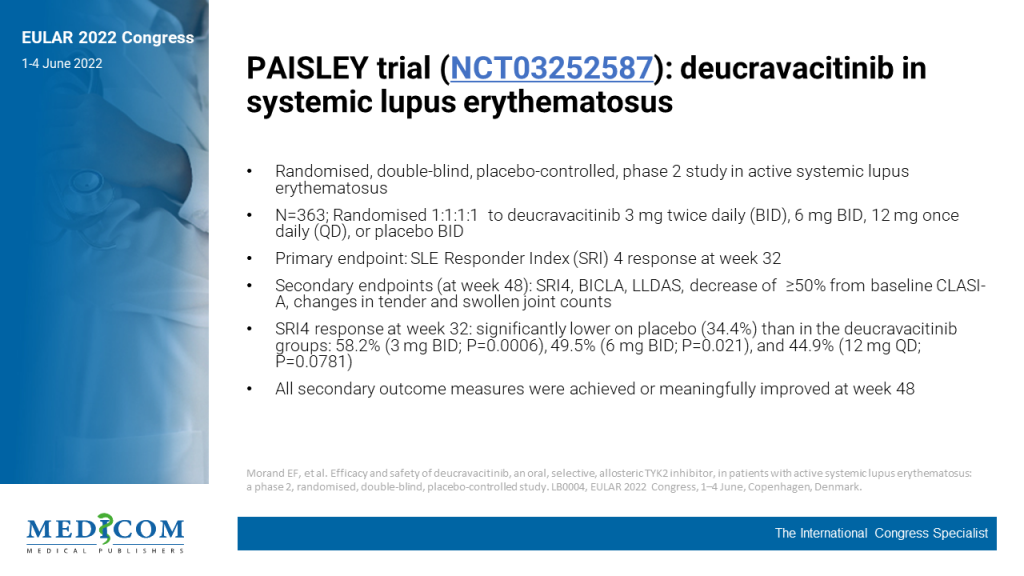

June 4, 2022

Downloadable 1-Page Selected Trial PowerPoint Slides

December 1, 2023

Incidence and risk factors for new-onset interstitial lung disease

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy