https://doi.org/10.55788/4d3e6d28

“Since we published our full guideline 2 years ago, there has been a lot of new evidence that required an update, because there are changes required to patient management,” Prof. Theresa McDonagh (King's College Hospital, UK) explained the motivation for the update [1]. She pointed out the multitude of important trial results that have emerged after the censoring date of 31 March 2021 for the former guidelines.

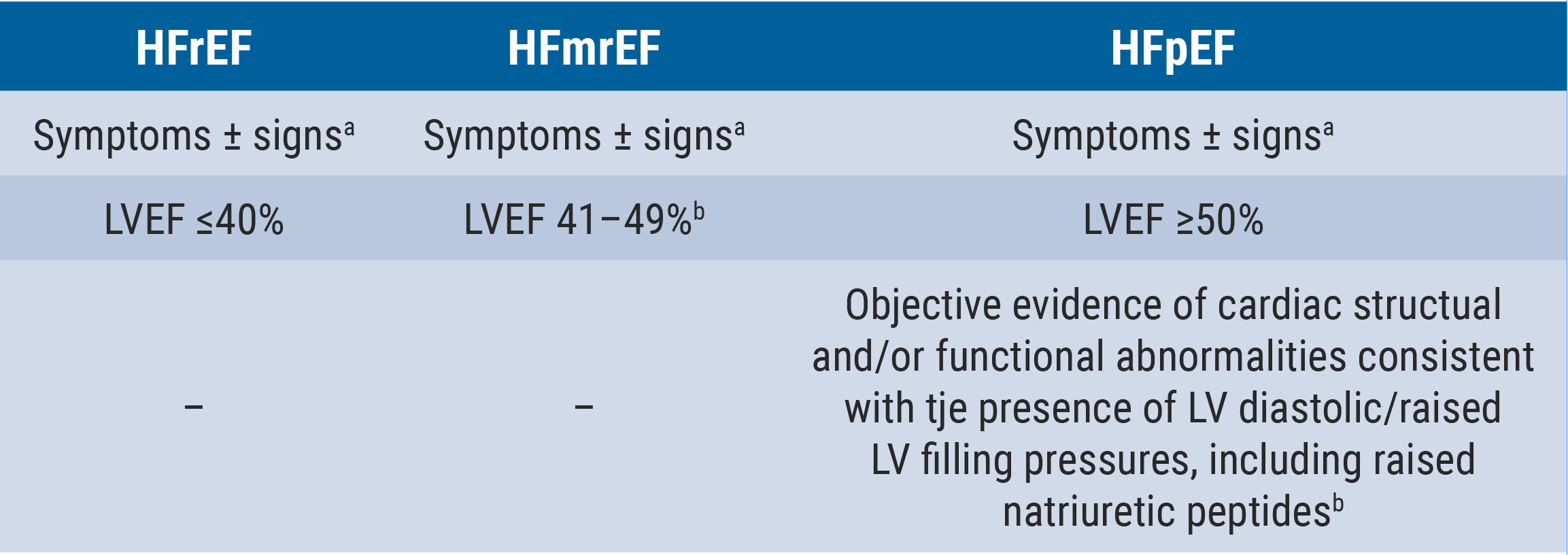

Starting with chronic HF, Prof. Roy Stuart Gardner (Golden Jubilee National Hospital, UK) underlined that the treatment algorithm for the management of patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has not been changed: instead of a sequential approach, patients should be started on key disease-modifying therapy as quickly and safely as possible [2]. He also reported that there was a task force deliberation on an alteration of nomenclature from the 3 phenotypes of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), HF with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and HFrEF, to only 2 types: HFrEF and HF with normal EF. This change was favoured by 71% but did not reach the necessary 75% consensus (see Table).

Table: Criteria defining the different phenotypes of heart failure [2]

HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

aSigns may not be present in the early stages of HF (especially in HFpEF) and in optimally treated patients.

bFor the diagnosis of HFmrEF, the presence of other evidence of structural heart disease (e.g. increased left atrial size, LV hypertrophy, or echocardiographic measures of impaired LV filling) makes the diagnosis more likely.

cFor the diagnosis of HFpEF, the greater the number of abnormalities present, the higher the likelihood of HFpEF.

Based on the results of the EMPEROR-Preserved (NCT03057951) and the DELIVER (NCT03619213) trials, 2 novel recommendations have been issued:

- an SGLT2 inhibitor (dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) is recommended for patients with HFmrEF, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation or cardiovascular (CV) death (class I); and

- an SGLT2 inhibitor (dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) is recommended for patients with HFpEF, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation or CV death (class I) [1–3].

Prof. Alexandre Mebazaa (Hôpital Lariboisière, France) stressed that optimal treatment of HF may substantially prolong survival [2,3]. “We know that giving the 4 classes of drugs at the optimal dose can reduce all-cause mortality by more than 50%, however, you know that all around the world and there are no exceptions, less than 5% of the patients have a combination of the 4 classes at the target dose.” Prof. Mebazaa alluded to inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system, aldosterone receptor antagonists, beta-blockers, and SGLT2 inhibitors. With regard to the now available, strong data concerning mortality and rehospitalisation for HF, a new recommendation has been issued:

- an intensive strategy of initiation and rapid up-titration of evidence-based treatment before discharge and during frequent and careful follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks following an HF hospitalisation is recommended, to reduce the risk of HF rehospitalisation or death (class I).

Prof. Mebazaa further advised particular attention should be paid to symptoms and signs of congestion, blood pressure, heart rate, NT-proBNP values, potassium concentrations, and estimated glomerular filtration rate to make sure that a patient is going in the right direction during the follow-up visits.

Comorbidities: important to manage

“There are some important comorbidities like diabetes, iron deficiency, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) that are strongly related with the pathophysiology of HF; all of them create a special metabolic milieu and together promote the progression of HF; therefore, they are of very high importance,” Prof. Ewa Jankowska (Wroclaw Medical University, Poland) explained [2,3]. Prof. Marianna Adamo (Civil Hospital of Brescia, Italy) focused on new recommendations for prevention with regard to diabetes and nephropathy, which are also based on new data from randomised-controlled trials as well as metanalyses:

- for patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) and CKD, SGLT2 inhibitors (dapagliflozin or empagliflozin) are recommended, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation or CV death (class I); and

- for patients with T2DM and CKD, finerenone is recommended, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation (class I).

Iron deficiency in itself is seen as an important factor for patients with HF. “Treating iron deficiency with intravenous iron is not related to the direct effect of erythropoiesis. Patients who are not anaemic benefitted equally to those who are anaemic,” Prof. Jankowska stated. The amelioration of quality-of-life is an important factor in favour of iron repletion and recent results merited a class I recommendation. As for hard clinical endpoints, the outcomes were not quite as strong, leading to a class IIa recommendation:

- intravenous iron supplementation is recommended in symptomatic patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF and iron deficiency, to alleviate HF symptoms and improve quality-of-life (class I); and

- intravenous iron supplementation with ferric carboxymaltose or ferric derisomaltose should be considered in symptomatic patients with HFrEF and HFmrEF and iron deficiency, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation (class IIa).

Prof. Jankowska furthermore stressed that oral iron does not improve exercise capacity in patients with HF.

- Presentations in session: ‘2023 ESC Guidelines Overview,’ ESC Congress 2023, 25–28 August, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Presentations in session: ‘2023 Focused update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure,’ ESC Congress 2023, 25–28 August, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- McDonagh TA, et al. Eur Heart J. 2023; Aug 25. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad195.

Copyright ©2023 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

« Should we use anticoagulation in AHRE to prevent stroke? Next Article

HEART-FID: Is intravenous ferric carboxymaltose helpful in HFrEF with iron deficiency? »

Table of Contents: ESC 2023

Featured articles

How to manage arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19?

2023 ESC Guidelines & Updates

Heart failure: the 2023 update

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies

Cardiovascular disease and diabetes: new guidelines

Guidelines for the management of endocarditis

Trial Updates in Heart Failure

Traditional Chinese medicine successful in HFrEF

CRT upgrade benefits patients with HFrEF and an ICD

Catheter ablation saves lives in end-stage HF with AF

Meta-analysis: Does FCM improve clinical outcomes in HF?

HEART-FID: Is intravenous ferric carboxymaltose helpful in HFrEF with iron deficiency?

Natriuresis-guided diuretic therapy to facilitate decongestion in acute HF

DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF

STEP-HFpEF: Semaglutide safe and efficacious in HFpEF plus obesity

Key Research on Prevention

Does colchicine prevent perioperative AF and MINS?

Diagnostic tool doubles cardiovascular diagnoses in patients with COPD or diabetes

Inorganic nitrate strongly reduces CIN in high-risk patients undergoing angiography

Finetuning Antiplatelet and Anticoagulation Therapy

Should we use anticoagulation in AHRE to prevent stroke?

Results of FRAIL-AF trial suggest increased bleeding risk with DOACs

The optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy in cancer patients with DVT

DAPT or clopidogrel monotherapy after stenting in high-risk East-Asian patients?

Assets for ACS and PCI Optimisation

Immediate or staged revascularisation in STEMI plus multivessel disease?

Lp(a) and cardiovascular events: which test is the best?

No benefit of extracorporeal life support in MI plus cardiogenic shock

Functional revascularisation outperforms culprit-only strategy in older MI patients

Can aspirin be omitted after PCI in patients with high bleeding risk?

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis

OCTOBER trial: OCT-guided PCI improves clinical outcomes in bifurcation lesions

Other

Minimising atrial pacing does not reduce the risk for AF in sinus node disease

ARAMIS: Can anakinra alleviate acute myocarditis?

Expedited transfer to a specialised centre does not improve cardiac arrest outcomes

Acoramidis improves survival and functional status in ATTR-CM

Related Articles

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis

ESC 2023 Highlights Podcast

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com