https://doi.org/10.55788/e9961534

The 2023 ESC Guidelines emphasise the need to screen all diabetic patients for CVD and chronic kidney disease (CKD), and it is advised to tailor further management according to individual risk assessment (see Figure) [1–3]. “We have developed a new risk prediction tool, called SCORE2-Diabetes,” Prof. Emanuele Di Angelantonio (University of Cambridge, UK) indicated. It serves to estimate the 10-year risk of fatal and non-fatal CVD events for the individual patient. Besides including known conventional and specific risk factors, it also incorporates a calibration for different risk regions in Europe. As of now, assessment with SCORE2-Diabetes is recommended for patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) without symptomatic atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) or severe target-organ damage (class I).

Figure: Central treatment strategies according to concomitant diagnoses in T2DM. Modified from [3]

ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; HF, heart failure; SGLT2, sodium-glucose co-transporter-2; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

aGLP-1 RAs with proven cardiovascular benefit: liraglutide, semaglutide s.c., dulaglutide, efpeglenatide. bSGLT2 inhibitors with proven cardiovascular benefit: empagliflozin, canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, sotagliflozin. CEmpagliflozin, dapagliflozin, sotagliflozin in HFrEF; empagliflozin, dapagliflozin in HFpEF and HFmrEF. dCanagliflozin, empagliflozin, dapagliflozin.

When T2DM and ASCVD are present

“The new guidelines introduce a novel concept, with special attention to the proven CV benefit or proven safety of glucose-lowering medication,” Prof. Nikolaus Marx (RWTH University Hospital Aachen, Germany) stressed. He also underlined that GLP-1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors are recommended for CV risk reduction independent of the HbA1c result and concomitant glucose-lowering medication (class I). The new recommendations further include that:

- it is recommended to prioritise the use of glucose-lowering agents with proven CV benefit, followed by agents with proven CV safety, over agents without proven CV benefit or proven CV safety (class I);

- it is recommended to switch glucose-lowering treatment from agents without proven CV benefit or proven safety to agents with proven CV benefit (class I);

- if additional glucose control is needed, metformin should be considered for patients with T2DM and ASCVD (class IIa); and

- if additional glucose control is needed, pioglitazone may be considered for patients with T2DM and ASCVD without heart failure (HF) (class IIb).

“It is of the utmost importance to identify patients with both HF and T2DM,” Dr Katharina Schuett (RWTH University Hospital Aachen, Germany) stated. In the 2023 Guidelines, a systematic survey for HF symptoms and/or signs of HF is recommended at each clinical encounter for all patients with diabetes (class I). Diagnostics in case of suspected HF comprise a recommendation for a 12-lead ECG, transthoracic echocardiography, a chest X-ray, and routine blood tests for comorbidities including blood count, urea, creatinine, electrolytes, thyroid function, lipids, and iron status (all class I). Importantly, in case of suspected HF, BNP/NT-pro BNP testing is also recommended (class I).

As for new therapeutic strategies, the following advice is given:

- SGLT2 inhibitors (i.e. dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, or sotagliflozin) are recommended for all patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and T2DM, to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation and CV death (class I);

- an intensive strategy of early initiation of evidence-based treatment (SGLT2 inhibitors, ARNI/ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and MRAs) with rapid up-titration to trial-defined target doses starting before discharge and with frequent follow-up visits in the first 6 weeks following HF hospitalisation, is recommended to reduce re-admissions or mortality (class I); and

- empagliflozin or dapagliflozin are recommended for patients with T2DM and left-ventricular EF >40% (HFmEF and HFpEF), to reduce the risk of HF hospitalisation or CV death (class I).

Prof. Dirk Müller-Wieland (RWTH University Hospital Aachen, Germany) stressed that the aim of treatment for patients with CKD and T2DM is to reduce both the CV risk and the kidney failure risk. As a first step to identifying these patients, it is recommended that patients with diabetes are routinely screened for kidney disease by assessing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) (class I). Amid the presented new class I recommendations were:

- SGLT2 inhibitors (canagliflozin, empagliflozin, or dapagliflozin) are recommended for patients with T2DM and CKD with an eGFR ≥20 mL/min/1.73 m2, to reduce the risk of CVD and kidney failure;

- finerenone is recommended in addition to an ACE inhibitor or ARB for patients with T2DM and eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 with a UACR ≥30 mg/mmol (≥300 mg/g), or eGFR 25–60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and UACR ≥3 mg/mmol (≥30 mg/g) to reduce CV events and kidney failure;

- intensive LDL-C lowering with statins or a statin/ezetimibe combination is recommended; and

- low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (75–100 mg once daily) is recommended for patients with CKD and ASCVD.

“Start treatment early, don’t wait for the nephrologist,” was a key message conveyed by Prof. Müller-Wieland. A kidney specialist’s advice may be considered for managing raised serum phosphate, other evidence of CKD–Mineral and Bone Disorder, and renal anaemia (class IIb).

Antithrombotic treatments

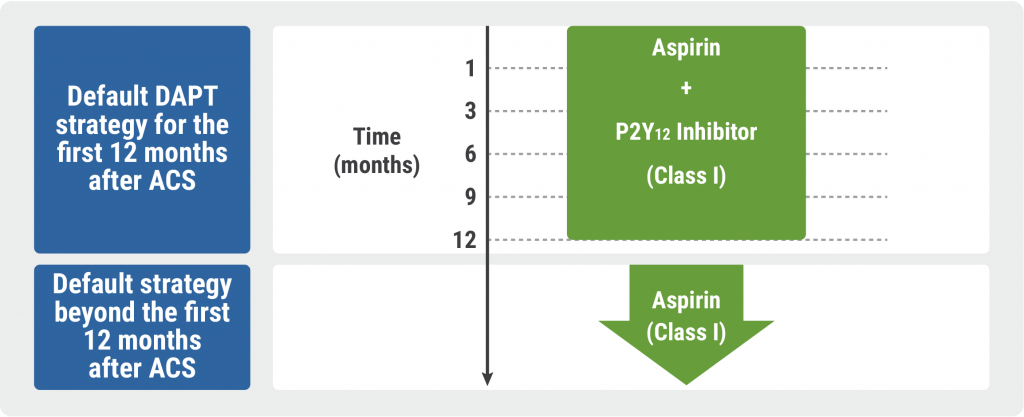

Prof. Bianca Rocca (Catholic University School of Medicine, Italy) emphasised that antithrombotic therapy is central in the management of CVD associated with diabetes. New and revised recommendations are especially concerned with acute (ACS) and chronic coronary syndromes (CCS), and the prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding:

- clopidogrel 75 mg once daily following appropriate loading (e.g. 600 mg or at least 5 days already on maintenance therapy) is recommended in addition to acetylsalicylic acid for 6 months, following coronary stenting for patients with CCS, irrespective of stent type, unless a shorter duration is indicated due to the risk or occurrence of life-threatening bleeding (class I);

- for patients with diabetes and ACS treated with dual antiplatelet therapy who are undergoing CABG and do not require long-term oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy, resuming a P2Y12-receptor inhibitor as soon as deemed safe after surgery and continuing it up to 12 months is recommended (class I);

- adding very low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) to low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for long-term prevention of serious vascular events should be considered for patients with diabetes and CCS or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease without high bleeding risk (class IIa);

- for patients with ACS or CCS and diabetes undergoing coronary stent implantation and having an indication for anticoagulation, prolonging triple therapy with low-dose acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, and an OAC should be considered up to 1 month (class IIa). A treatment period of up to 3 months may be considered (class IIb) if the thrombotic risk outweighs the bleeding risk in the individual patient;

- when antithrombotic drugs are used in combination, proton pump inhibitors are recommended to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding (class I); and

- when a single antiplatelet or anticoagulant drug is used, proton pump inhibitors should be considered to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding, considering the bleeding risk of the individual patient (class IIa).

As another important overall aspect, Prof. Massimo Federici (University of Rome Tor Vergata, Italy) mentioned that the new guidelines endorse a person-centred approach in order to facilitate shared decision-making.

- Presentations in session: ‘2023 ESC Guidelines Overview,’ ESC Congress 2023, 25–28 August, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Presentations in session: ‘2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Diabetes’, ESC Congress 2023, 25–28 August, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Marx N, et al. Eur Heart J. 2023; Aug 25. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad192.

Copyright ©2023 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« Does colchicine prevent perioperative AF and MINS? Next Article

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis »

« Does colchicine prevent perioperative AF and MINS? Next Article

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis »

Table of Contents: ESC 2023

Featured articles

How to manage arterial thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19?

2023 ESC Guidelines & Updates

Heart failure: the 2023 update

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies

Cardiovascular disease and diabetes: new guidelines

Guidelines for the management of endocarditis

Trial Updates in Heart Failure

Traditional Chinese medicine successful in HFrEF

CRT upgrade benefits patients with HFrEF and an ICD

Catheter ablation saves lives in end-stage HF with AF

Meta-analysis: Does FCM improve clinical outcomes in HF?

HEART-FID: Is intravenous ferric carboxymaltose helpful in HFrEF with iron deficiency?

Natriuresis-guided diuretic therapy to facilitate decongestion in acute HF

DICTATE-AHF: Early dapagliflozin to manage acute HF

STEP-HFpEF: Semaglutide safe and efficacious in HFpEF plus obesity

Key Research on Prevention

Does colchicine prevent perioperative AF and MINS?

Diagnostic tool doubles cardiovascular diagnoses in patients with COPD or diabetes

Inorganic nitrate strongly reduces CIN in high-risk patients undergoing angiography

Finetuning Antiplatelet and Anticoagulation Therapy

Should we use anticoagulation in AHRE to prevent stroke?

Results of FRAIL-AF trial suggest increased bleeding risk with DOACs

The optimal duration of anticoagulation therapy in cancer patients with DVT

DAPT or clopidogrel monotherapy after stenting in high-risk East-Asian patients?

Assets for ACS and PCI Optimisation

Immediate or staged revascularisation in STEMI plus multivessel disease?

Lp(a) and cardiovascular events: which test is the best?

No benefit of extracorporeal life support in MI plus cardiogenic shock

Functional revascularisation outperforms culprit-only strategy in older MI patients

Can aspirin be omitted after PCI in patients with high bleeding risk?

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis

OCTOBER trial: OCT-guided PCI improves clinical outcomes in bifurcation lesions

Other

Minimising atrial pacing does not reduce the risk for AF in sinus node disease

ARAMIS: Can anakinra alleviate acute myocarditis?

Expedited transfer to a specialised centre does not improve cardiac arrest outcomes

Acoramidis improves survival and functional status in ATTR-CM

Related Articles

October 30, 2023

STEP-HFpEF: Semaglutide safe and efficacious in HFpEF plus obesity

October 30, 2023

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

October 30, 2023

Angiography vs OCT vs IVUS guidance for PCI: a network meta-analysis

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com