https://doi.org/10.55788/ae433730

“Since 2019, there has been a paradigm shift in our understanding of the pathophysiology of myocardial ischaemia and CCS,” stated Prof. Christiaan Vrints (University Hospital Antwerp, Belgium) [1]. This led to an updated, more comprehensive definition of the in 2019 introduced term ‘CCS’ that includes a range of clinical presentations or syndromes that arise due to structural or functional alterations related to chronic diseases of the coronary arteries or microcirculation [1–3]. Prof. Vrints also accentuated that the underlying pathophysiology is complex, as structural and functional abnormalities may present both at the epicardial and microvascular levels.

The new guidelines recommend a 4-step approach to the management of suspected CCS. Step 1 starts with a detailed assessment of cardiovascular risk factors, medical history, and symptom characteristics (class I), alongside a resting ECG and biochemistry. Step 2 involves further cardiac examination to rule out left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and valvular heart disease, and to evaluate the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) using a new and better-calibrated likelihood model (see Figure). “The other models were essentially overestimating the probability of obstructive coronary disease,” Dr Francisco Xavier Rosselló (Son Espases University Hospital, Spain) commented on the new guidance, which further details:

- It is recommended to estimate the pre-test likelihood of obstructive epicardial CAD using the risk factor-weighted clinical likelihood model (class I).

- It is recommended to use additional clinical data (e.g. examination of peripheral arteries, resting ECG, resting echocardiography, presence of vascular calcifications on previously performed imaging tests) to adjust the estimate yielded by the risk factor-weighted clinical likelihood model (class I).

- In individuals with a very low (≤5%) pre-test likelihood of obstructive CAD, deferral of further diagnostic tests should be considered (class IIa).

- In individuals with a low (>5–15%) pre-test likelihood of obstructive CAD, coronary artery calcium scoring (CACS) should be considered to reclassify subjects and to identify more individuals with very low (≤5%) CACS-weighted clinical likelihood (class IIa).

The third step in this approach aims at confirming the diagnosis and estimating the event risk tailored to the clinical likelihood of obstructive CAD. In individuals with low-to-moderate (>5–50%) pre-test likelihood, a coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is now recommended (class I). In moderate-risk patients, functional imaging has the same class of recommendation as CCTA. “For high-risk patients, functional imaging has a class I indication, while, for patients with very high risk, invasive parameter angiography has a class I indication,” Dr Rosselló informed.

Do not overlook angina or ischaemia with no obstructive CAD

“Patients with obstructive CAD only constitute the very tip of the iceberg, up to 50% of the men and 70% of the women with suspected CCS do not have obstructive CAD and they may suffer from angina with non-obstructive CAD [ANOCA] or ischaemia [INOCA],” Prof. Vrints highlighted. ANOCA and INOCA received new recommendations for diagnostics and management:

- Invasive coronary angiography with the availability of invasive functional assessments is recommended to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of obstructive CAD or ANOCA/INOCA in individuals with an uncertain diagnosis on non-invasive testing (class I).

- In symptomatic patients with ANOCA/INOCA, medical therapy based on coronary functional test results should be considered to improve symptoms and quality-of-life (class IIa).

CCS treatment

The last step in the recommended approach to the initial management of suspected CCS is all about treatment and includes lifestyle and risk modification, medication, and revascularisation. A new class I recommendation advises tailoring the selection of anti-anginal drugs to patient characteristics, comorbidities, concomitant medications, treatment tolerability, and underlying pathophysiology of angina, also considering local drug availability and costs.

“The guideline does not specify first- or second-line treatment but does give an order of strength of recommendation with beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates still holding the strongest class I or IIa,” Prof. Felicita Andreotti (Gemelli University Hospital, Italy) detailed. Further new recommendations on therapy include:

- In patients with CCS and a prior MI or PCI, clopidogrel 75 mg daily is recommended as a safe and effective alternative to aspirin monotherapy (class I).

- In patients with CCS without prior MI or revascularisation but with evidence of significant obstructive CAD, aspirin 75–100 mg daily is recommended lifelong (class I).

- The GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide should be considered in patients with CCS without diabetes but with overweight or obesity (BMI >27 kg/m2), to reduce cardiovascular mortality, MI, or stroke (class IIa).

- In patients with CCS with atherosclerotic CAD, low-dose colchicine (0.5 mg daily) should be considered to reduce MI, stroke, and need for revascularisation (class IIa).

Dr Konstantinos Koskinas (Bern University Hospital, Switzerland) encouraged his colleagues to take time to inform their patients and involve them in shared decision-making in an effort to increase long-term adherence to therapy.

Special guidance on revascularisation

For revascularisations, the guidelines recommend that physicians select the most appropriate modality based on the patient profile, coronary anatomy, procedural factors, LVEF, patient preferences, and outcome expectations (class I). Image guidance using intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography for PCI is recommended for anatomically complex lesions (class I). In CCS with left main disease, important new class I recommendations on surgery have been issued:

- In patients with CCS at low surgical risk with significant left main coronary stenosis, coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is recommended:

- over medical therapy alone to improve survival,

- as the overall preferred revascularisation mode over PCI, given the lower risk of spontaneous MI and repeat revascularisation.

- In patients with CCS with significant left main coronary stenosis of low complexity (SYNTAX score ≤22), in whom PCI can provide equivalent completeness of revascularisation to that of CABG, PCI is recommended as an alternative to CABG, given its lower invasiveness and non-inferior survival.

- In patients with CCS at low surgical risk with significant left main coronary stenosis, coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) is recommended:

- Presentations in Session ‘2024 ESC Guidelines Overview,’ ESC Congress 2024, 30 Aug–02 Sept, London, UK.

- Presentations in Session ‘2024 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Chronic Coronary Syndromes,’ ESC Congress 2024, 30 Aug–02 Sept, London, UK.

- Vrints C, et al. Eur Heart J. 2024. DOI : 10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177.

Copyright ©2024 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation Next Article

Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension »

« Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation Next Article

Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension »

Table of Contents: ESC 2024

Featured articles

Meet the Expert: Dr Abdullahi Mohamed on Iron Deficiency in Patients with HF

2024 ESC Guidelines in a Nutshell

Guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension

Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes

Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation

Guidelines for the management of peripheral artery and aortic diseases

Crossing Borders in Arrhythmia

EPIC-CAD: What is the best antithrombotic approach in high-risk AF plus stable CAD?

OCEANIC-AF: Asundexian inferior to apixaban for ischaemic stroke prevention in AF

MIRACLE-AF: Elegant solution to improve AF care in rural China

SUPPRESS-AF: What is the value of adding LVA ablation to PVI in AF?

Clever Ideas for Coronary Artery Disease

ABYSS: Can beta-blocker safely be interrupted post-MI?

SWEDEGRAFT: Can a no-touch vein harvesting technique improve outcomes in CABG?

Bioadaptor meets expectations in reducing target lesion failures in coronary artery disease

REC-CAGEFREE I: Can we avoid permanent stenting with drug-coated balloons?

OCCUPI: OCT-guided PCI improves outcomes in complex CAD

Highway to Hypertension Control

Low-dose 3-drug pill GMRx2 shows promise in lowering BP

Is administering BP medication in the evening better than in the morning?

VERONICA: Improving BP control in Africa with a simple strategy

High-end Trials in Heart Failure

FINEARTS-HF: Finerenone improves outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

MRAs show varied efficacy in heart failure across ejection fractions

MATTERHORN: Transcatheter repair matches surgery for HF with secondary mitral regurgitation

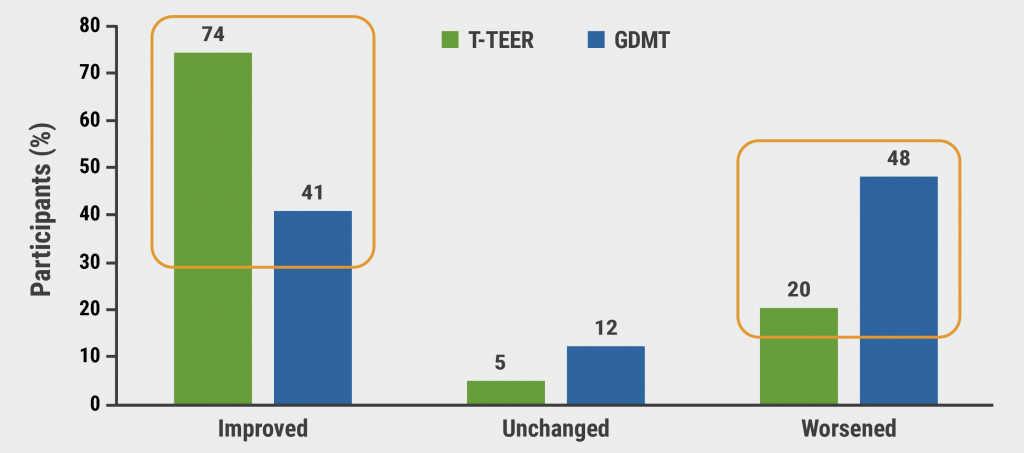

RESHAPE-HF2: Not a “tie-breaker” for TEER in heart failure

Practical Gains in Screening and Diagnostics

STEEER-AF: Shockingly low adherence to ESC atrial fibrillation guidelines

SCOFF: To fast or not to fast, that’s the question

WESTCOR-POC: Point-of-care hs-troponin testing increases emergency department efficiency

PROTEUS: Can AI improve decision-making around stress echocardiography?

RAPIDxAI: Can AI-augmented chest pain assessment improve cardiovascular outcomes?

Miscellaneous Achievements in Cardiology

HELIOS-B: Vutrisiran candidate for SoC in ATTR cardiomyopathy

Does RAS inhibitor discontinuation affect outcomes after non-cardiac surgery?

Novel approach to managing severe tricuspid regurgitation proves its value

NOTION-3: TAVI plus PCI improves outcomes in CAD plus severe aortic stenosis

RHEIA: TAVI outperformed surgery in women with aortic stenosis

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com