Functional bowel disorders account for most referrals to gastroenterologists and have a prevalence of around 25% in the general population [3]. IBS is one of the most frequent functional disorders, with a prevalence of about 10% in Western countries. Due to its chronic nature, up to 50% of patients will consult a physician for their IBS symptoms. IBS is characterised by the presence of recurrent abdominal pain, on average at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months, and it is associated with 2 or more of the following symptoms: symptoms related to defecation, change in frequency of stool, or change in appearance of stool.

Dr Corsetti stressed the importance of explaining to the patient that it can be hard to find a balance between treating constipation without first worsening the pain. She also warned that opioid use is not a problem confined to the United States: she was “shocked” to find its use to be widespread in the United Kingdom as well. There is no evidence to suggest that opioids can offer long-term relief from IBS-related pain. They can paradoxically increase bowel pain: narcotic bowel syndrome (NBS) or opioid-induced hyperalgesia are known adverse effects of opioid use.

Dr Corsetti also emphasised that IBS treatment starts at the time of diagnosis, meaning that the described symptoms directly influence the choice of treatment(s) for each particular individual case. “The first consultation is part of the treatment,” as she phrased it. She offered the following advice:

- Evaluate symptoms carefully, showing an interest in the patients’ clinical history.

- Never say “you do not have anything serious,” but make a precise diagnosis (i.e. IBS functional dyspepsia, functional constipation, NBS).

- Explain in simple terminology what the most likely cause of the symptoms is.

- Reassure the patients that IBS does not increase the risk of cancer or organ disease.

- Involve the patients in the decision on how to treat the pain.

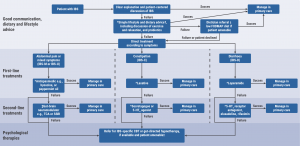

Treatment options according to the 2021 IBS Guidelines of the British Society of Gastroenterology are shown in the Figure. Dr Corsetti advised caution with restrictive diets. Supervision by a dietician is very important. Patients have often already restricted themselves in their diet “in ways that do not make any sense;” as many as 10% suffer from an avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.

Figure: Treatment options according to BSG IBS Guidelines 2021 [2]

Reprinted from Vasant DH, et al. Gut. 2021;70(7):1214–40. Copyright 2021, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

*Review efficacy after 3 months of treatment and discontinue if no response. †As per the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence IBS dietary advice sheet, plus consider ispaghula. ‡TCAs should be first choice, starting at a dose of 10 mg at night, and titrating slowly (e.g. by 10 mg/week) according to response and tolerability. Continue for at least 6 months if the patient reports symptomatic response. ±Where available locally, and based on patient preference, psychological therapies can be considered at an earlier stage, but are recommended strongly when symptoms are refractory to drug treatment for 12 months.

5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; FODMAP, fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides and monosaccharides and polyols; IBS-C, IBS with constipation; IBS-D, IBS with diarrhoea; IBS-M, IBS with mixed bowel habits; IBS-U, IBS unclassified; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA, tricyclic antidepressant.

Evidence is present, albeit limited, on the effectiveness of neuromodulators in IBS. Dr Corsetti herself has used these medications since the beginning of her 20 years of clinical experience. She shared some approaches she has developed over the years in collaboration with psychiatrists. She frequently starts a tricyclic antidepressant, or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) if anxiety and depression are major components of the patients’ problem. She starts with very low doses (e. g. amitriptyline 5–10 mg; citalopram 5–10 mg; sertraline 25–50 mg) daily for 10–20 days and she explains that the pain and/or anxiety may worsen at first. To assess the response, a follow-up appointment is booked after 2 months. In case of suboptimal response, combining neuromodulators may be considered.

- Corsetti M. Managing psychiatric comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome: stuck in a revolving door? S.17.04, ECNP 2021 Congress, 2–5 October.

- Vasant DH, et al. Gut. 2021;70(7):1214–40.

- Sperber AD, et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99–114.

Copyright ©2021 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« ‘Glimpse of hope’ when anti-CD20 drugs limit vaccine antibodies Next Article

Anxiolytic activity of a novel orexin-1 receptor antagonist »

« ‘Glimpse of hope’ when anti-CD20 drugs limit vaccine antibodies Next Article

Anxiolytic activity of a novel orexin-1 receptor antagonist »

Table of Contents: ECNP 2021

Featured articles

Anxiety and Stress

Anxiolytic activity of a novel orexin-1 receptor antagonist

Autism

Finding biomarkers for improved patient stratification

Behavioural Disorders

Sex similarities and differences in the neurobiology of aggression

Risky driving and lifestyle may have a common psychobiological basis

Cannabidiol for cannabis cessation shows positive results

Somatic comorbidities of ADHD: epidemiological and genetic data

Novel approaches to understanding the social brain

COVID-19

Alcohol consumption during lockdown

Post-COVID-19 depression responds well to SSRIs

Impact of COVID-19 on patients with psychotic disorders

Mood Disorders

Depression and brain structures associations across a lifespan

BDNF/TrkB pathway promising alternative for new antidepressants

Zuranolone reduces symptoms of major depression

Vortioxetine effectively reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety

Esketamine outperforms real-world management for treatment-resistant depression: preliminary results

Smartphone interventions in bipolar disorder: a position paper

Connecting, challenging, and empowering youth through their smartphone

Personality Disorders

Evaluating vafidemstat for the treatment of borderline personality disorder

Deep brain stimulation effective in the treatment of refractory OCD

Psychotic Disorders

Why antipsychotics cause weight gain

Roluperidone improves negative symptoms in schizophrenia

Other

Brain Prize Lecture: Prof. Jes Olesen on migraine

Laxative may improve cognitive performance

Related Articles

November 26, 2021

Brain Prize Lecture: Prof. Jes Olesen on migraine

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com