We will be discussing a very important topic today, but first can you tell us who you are and what the focus of your research is?

“I am a geriatrician and a palliative medicine physician. I have been providing care to predominantly home-bound older adults for over a decade. These include people who are healthy as well as people with serious illness and life-limiting illness. I provide care in a primary care capacity but also to patients who are in hospice with a prognosis of less than 6 months. I'm a clinician first and foremost, and as part of that I have a research career driven by the things that I observe with my own patients that make me wonder: How can I improve people's health and wellbeing?”

“This brought me to studying and understanding loneliness. I've been interested in understanding how loneliness affects older adults’ ability to stay independent, as well as their risk of mortality, but also what we do about it, since there's many community-based organisations that work with older adults. These organisations have great programs and I'm curious about whether they actually impact people's health and wellbeing.”

What are the metrics used in this particular research?

“There are standard definitions for loneliness and isolation. It is important to mention both, because loneliness and isolation are related but different. Loneliness is the subjective feeling of being alone and social isolation is really more about the quantifiable number of relationships. Someone can have a lot of relationships and not be isolated, but still feel lonely, and vice versa.”

“There are standardised measures for loneliness available. In the United States, the Three Item Loneliness questionnaire is the most commonly used measure. It asks if people feel left out, if they feel isolated, or if they lack companionship. If they have this feeling all the time, this is classed as more severe loneliness; if someone has this feeling some of the time, it's more moderate or mild loneliness. For social isolation, there are also several different measures available. A common measure, recommended by the Institute of Medicine to be included in electronic medical records, is the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index.”

“The importance of this is that these are standard definitions, they can be measured. Even for busy clinicians and primary care providers, this is something that can be done in practice. My colleague Julianne Holt-Lunstad and I wrote an article in the New England Journal of Medicine which outlined a framework for clinicians [1]. We called it the EAR framework, with the idea of providing a listening ear. The E stands for Educate, with the aim to educate patients about the risks of loneliness and isolation. The A stands for Assess, in order to use these standardised measures. And the R is for Respond and Reassess, to ensure building a track record over time, much like we do with other measures in healthcare. In a couple of months a physician can reassess to see if what has been offered as a solution has actually made an impact.”

Can you tell us about the prevalence of loneliness and social isolation in older adults?

“The initial research that I conducted in 2012 had a prevalence rate of 43% in people over the age of 60, and that's for any type of loneliness. This was paralleled by the recent Surgeon General’s Advisory report [2]. For social isolation, it's probably about 1 in 4 older adults. These are not insignificant findings; loneliness and social isolation are very prevalent. We are seeing this in our practices and probably even if we're not directly assessing. Many of us may be seeing patients that haven't identified it themselves or feel uncomfortable talking about it, or maybe we as clinicians don't know how to talk about it.”

You mentioned the recent Surgeon General’s Advisory report about loneliness and social isolation. Could you tell me what was your interpretation of that report and was it a call to action? And if so, how can clinicians respond appropriately?

“I was one of the reviewers of the Surgeon General’s Advisory report, so I was very excited when it was published. This is a follow up of a 2020 report from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine which already demonstrated that the healthcare sector shouldn’t ignore this topic. Following this 2020 report, we had 3 years of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Surgeon General who openly discussed his own experience with loneliness. The Surgeon General’s Advisory report focuses on the evidence for the dramatic health effects and is absolutely a call to action that this is a public health priority in the United States and even globally, since the World Health Organization is also starting to tackle this topic.”

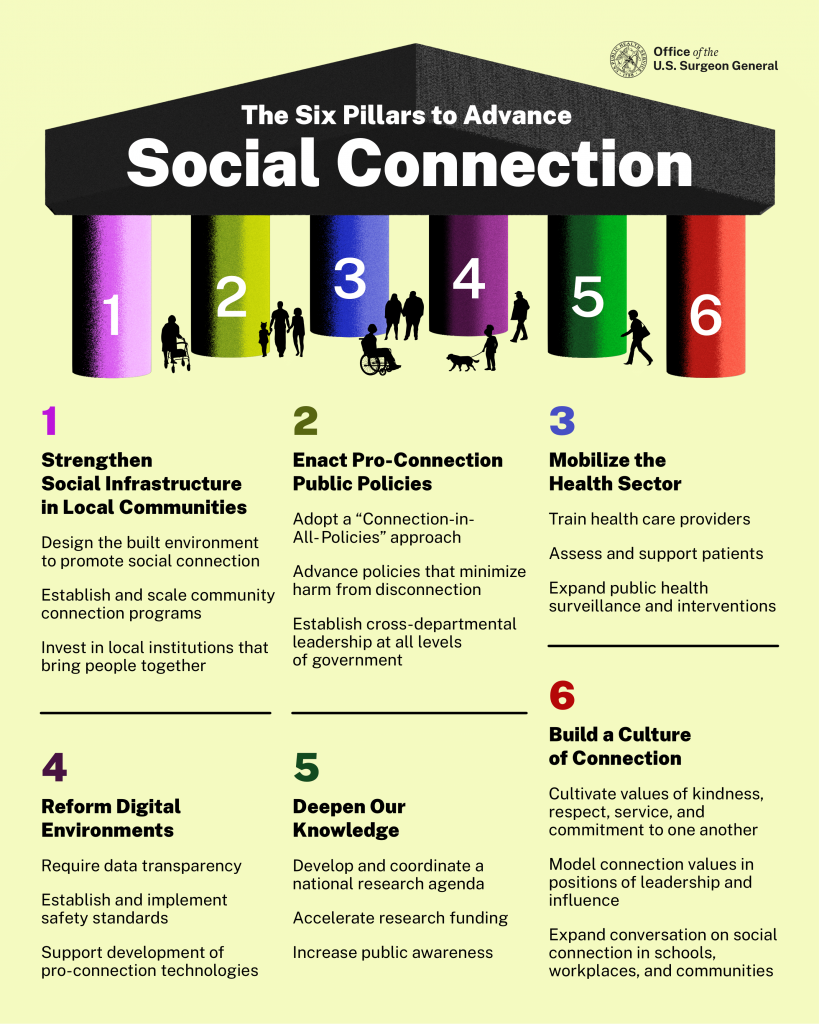

“The Surgeon General explains that there are 6 pillars of social connection, and that it's all about strengthening the fabric of our connection. The first pillar is about strengthening social infrastructure in our individual communities, meaning that part of the solution needs to happen locally. The second pillar is about enacting pro-connection public policies, more at a global level. The third one is mobilizing the health sector, which very much dovetails on the National Academy of Sciences report. The fourth pillar is about rethinking about digital environments and how interaction with technology and our digital world can help or hinder our social connections. The fifth is deepening our knowledge on this topic and, finally, the sixth pillar is about building a culture of connection (see Figure).”

Figure: The 6 pillars to advance social connection. Available from the Surgeon General’s Advisory on Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation [2].

What does the fifth pillar ‘Deepening our knowledge’ mean exactly? Does it refer to stimulating research in this area?

“There are a couple things to mention. It refers to research and also to public awareness. There has been more media attention, but that has not been translated into the knowledge base having a complete national agenda. Public health campaigns are important to help recognise that we need to prioritise our social health and our social connection if we do want to have prosperous, independent, long lives. With regards to furthering the research, it should focus on identifying programs and solutions that help, because the health effects of loneliness are very understood.”

How will this translate within the United States, among communities, and will this also translate to outside of the United States?

“First, there is the understanding that depending on where you live, the way people form social connections is different. Secondly, there is the understanding of when you’ve identified yourself as lonely, you need to find out if there are supports in your community to turn to for help with enhancing my social connections. Are there relationships that you could develop individually, which is a person’s own responsibility. Or are there programs that may help, which can be considered a responsibility of health plans, insurers, or government. Loneliness is impacting our health and needs a multi-stakeholder response. For example, there are a lot of comparisons made between the health effects of smoking and social connection, which are pretty similar. A lot of public health dollars are spent on smoking cessation and prevention. Should we be dedicating that same amount of funding towards social connection?”

What are some of the experiences that you've had with interventions? Could you describe what some of those look like?

“I've had the fortune of working with several different community organisations, and I'll highlight one because it's a published article with evidence behind the intervention [3]. This intervention was a program with the Curry Senior Center in San Francisco, situated in a neighbourhood with premature aging, high prevalence of comorbid illnesses and coexisting psychiatric illnesses, and a lot of unstable housing. In this neighbourhood, there were many older adults who were likely isolated and in need of social connection. The goal of this program was to connect the older adults to community services, but we found that the older adults just needed another person to connect with. When we paired clients, we found reductions in feelings of loneliness, reductions in the barriers to social isolation, and reductions in depression.

“The important question now is whether these programs can scale and can translate into other communities. We hope to receive more funding to further expand these programs and see how to replicate our findings in other settings.”

Are there cultures where geriatric social isolation is not as prevalent? What can we learn from these? Best practices?

“There's been a term called the Blue Zones. Blue Zones are communities where people have long life expectancies of up to 100 years old. The researchers discovered that longevity in these areas was absolutely based on social connection. When town structures are more geared towards socially connecting, there is an increased focus on good food, movement, and connection. I think it's really about what we value, how cities and people’s work are set up, and the value of intergenerational households as well.”

What’s next?

“There so many different things to do. We've been talking a lot about how to standardise measuring social connection in healthcare. I think if we do not measure it and do not include it in our standardised encounters with patients, we're not going to move anywhere. We don't know what we're missing and that can be very daunting.”

“We currently have a crisis in healthcare with primary care providers already feeling overstretched and thinking ‘This is one more thing to do’. I think the argument is that we are spending a lot of time on things that may not have the same impact on someone's life as social connection. Social connection may actually be a way to get better health outcomes, as well as a way for healthcare providers to better connect with their patients. It's amazing that I've seen that in practice, and then again in the research. So we need more integration of measuring loneliness and social isolation into our health system, which includes the electronic medical record.”

“From there, the next steps involve the concept of social prescribing. Europe is bit more advanced in recognising loneliness, and doctors think ‘I identify someone as lonely and I'd like to have a social prescription. Is that evidence based?’ And then there are policies that support treating the condition of loneliness in that individual. In the United States, we don’t have a single payer healthcare system, but a multimodal payment system that needs to have some buy-in from our health plans. It’s important to investigate how to implement best-practices where possible.

What are the take-home messages?

“I think the message is that, even though it can be very hard as a primary care physician because there are so many different measures already, it's incredible how impactful simply talking about the importance of social connection can be on our relationships with our patients and their longevity and wellbeing.”

- Holt-Lunstad J, Perissinotto C. Social Isolation and Loneliness as Medical Issues N Engl J Med. 2023;388(3):193-195.

- https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-social-connection-advisory.pdf

- Kotwal AA, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 Dec;69(12):3365-3376.

Copyright ©2023 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« EAN 2023 Highlights Podcast Next Article

Linking the Black Death with Crohn’s disease predisposition »

« EAN 2023 Highlights Podcast Next Article

Linking the Black Death with Crohn’s disease predisposition »

Related Articles

October 8, 2020

PPIs associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy