"It's clear that the sooner we intervene, the better the outcomes," Dr. Oussama Wazni of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, who is chief author of the STOP-AF study, told Reuters Health in a telephone interview. "I think this will change the guidelines," which currently recommend ablation only if drug therapy fails.

He also predicted that trying ablation first will save money over the long term because "a big percentage of patients in the drug group ended up with ablation anyway, so there's no cost savings" to trying drugs first.

The erratic heartbeat of atrial fibrillation makes the likelihood of stroke five- to seven-times greater. The condition affects roughly 1% to 2% of the population. With cryoablation, a supercold balloon, temporarily inflated in the heart, destroys the tissue that is sparking the irregular heartbeat.

Both studies appear in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The most dramatic result came from the 303-patient EARLY-AF trial, led by Dr. Jason Andrade of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada. It was funded in part by the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada, along with industry grants.

In that test, the 154 patients assigned to undergo ablation saw a 52% decline in the hazard of atrial tachyarrhythmia recurring by the one-year mark.

The rates were 42.9% with ablation versus 67.8% with conventional antiarrhythmic drugs (P<0.001), as measured by implantable cardiac monitoring.

When the team looked at atrial tachyarrhythmia that provoked symptoms, the rates were 11.0% with ablation and 26.2% with drug therapy, a 61% reduction.

The rates of serious events were comparable in the two groups.

Those results were also released Monday morning at the virtual American Heart Association Scientific Sessions meeting.

Dr. Wazni's STOP-AF study, funded by Medtronic, randomized 203 patients at 24 U.S. medical centers. All had recurrent symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and they had also not received rhythm-control therapy.

Pulmonary-vein isolation with a cryoballoon was done on 104. The research team used periodic 12-lead electrocardiography and telephone monitoring to gauge success of the therapy.

At the one-year point, ablation was judged to be successful in 74.6% of the patients and drug therapy worked for 45.0% (P<0.001). When the team excluded patients in the drug group who had not taken a therapeutic dose of their antiarrhythmic drug throughout the trial, the success rate in that group increased to 51%.

The procedure was not considered successful if the procedure itself failed, subsequent atrial fibrillation surgery or ablation was done, or Afib recurred after the first 90 days.

Two patients had a safety-related event in the ablation group. One had pericardial effusion during the first month after the procedure and a second had a heart attack seven days after ablation.

The rates of serious adverse events were identical in the two groups at 14%.

"A third of the patients in the drug-therapy group subsequently underwent ablation as a result of drug-related side effects or recurrence of arrhythmia," the researchers write.

In addition, "healthcare utilization seems to be much less in the ablation group than in the drug group," said Dr. Wazni.

Getting the best treatment first is important because "if you allow atrial fibrillation to go on unabated, the size of the left atrium can get bigger and contribute to more scar tissue formation. That can propagate atrial fibrillation and make it more difficult to manage," said Dr. Wazni.

In both studies, the researchers didn't begin looking for a primary endpoint until 90 days after the initiation of treatment to compensate for the time needed to recover from the ablation procedure or find the best drug dose.

"Although antiarrhythmic drug therapy is recommended before ablation in current guidelines, drug therapy fails to prevent atrial fibrillation recurrence in 43% to 67% of patients and has been associated with potentially serious proarrhythmic and extracardiac adverse effects," Dr. Wazni's team writes.

By Gene Emery

SOURCES: https://bit.ly/3f3ZblS and https://bit.ly/2KdvhjV The New England Journal of Medicine, online November 16, 2020.

Posted on

Previous Article

« Correcting iron deficiency protects heart failure patients from repeat hospital stay Next Article

Study supports routine physiologic assessment to guide revascularization »

« Correcting iron deficiency protects heart failure patients from repeat hospital stay Next Article

Study supports routine physiologic assessment to guide revascularization »

Related Articles

November 7, 2024

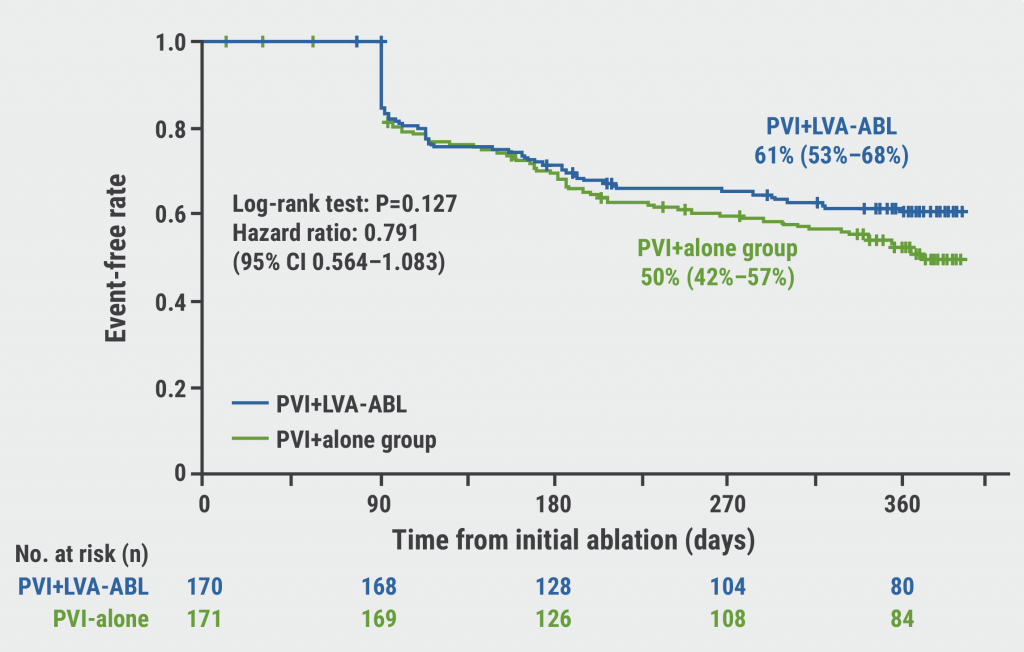

SUPPRESS-AF: What is the value of adding LVA ablation to PVI in AF?

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com