* Contributed equally

Affiliation

1. Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev and Gentofte, Copenhagen, Denmark 2. University of Copenhagen, Department of Clinical Medicine, Copenhagen, Denmark

* Contributed equally

Affiliation

Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev and Gentofte, Copenhagen, Denmark

Affiliation

1. Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Copenhagen University Hospital – Herlev and Gentofte, Copenhagen, Denmark 2. University of Copenhagen, Department of Clinical Medicine, Copenhagen, Denmark

Doi

https://doi.org/10.55788/3cc048d2

comorbidity in adult psoriasis

Psoriasis was once thought to only involve the skin, but today the disease is recognised as a chronic systemic disease associated with a high burden of comorbidities.1 Psoriatic arthritis is the most well-known comorbidity, which is considered as a disease entity with psoriasis, affecting ∼20% of the patients.2 There is an extensive list of other disorders that occur more frequently in patients with psoriasis such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), liver disease, the metabolic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, mental disorders, and malignancies.3 In this proceeding paper we will focus on two comorbidities with high clinical impact; cardiovascular disease and liver disease. Additionally, causal associations will be discussed.

Cardiovascular disease

CVD, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, is a leading cause of death globally4 highlighting the importance of sufficient treatment and prevention of the disease. Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of CVD, and reduced life expectancy as a consequence.5,6 In the early 1970s, the association between psoriasis and CVD was first suggested by a small retrospective study.7 Approximately 30 years later, a landmark study confirmed this link8 and since then, several epidemiological studies have showed similar findings.9–12 Some of these studies indicate that the risk of CVD is highest among young patients with severe psoriasis and that the risk increases with the severity of the disease.8,10 Further, the risk of CVD is observed to be equal to patients with diabetes, which is already a well-known risk factor of CVD.10 Additionally, subclinical atherosclerotic disease, detected by cardiovascular imaging studies including e.g., positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) and ultrasound imaging, is increased in patients with psoriasis.13–15 Indeed, multiple studies have been published the last three decades, providing strong evidence that patients with psoriasis have an increased risk of CVD and subclinical CVD.16–20

Let´s begin with the cardiovascular risk factors.

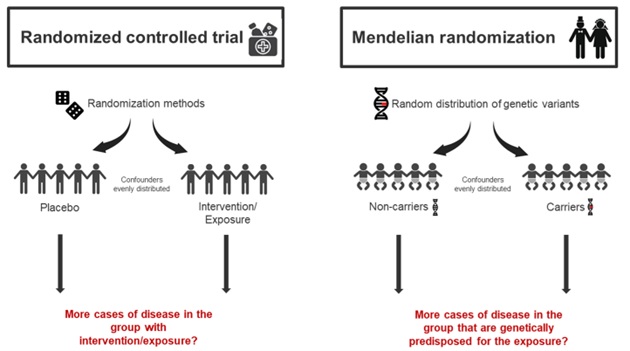

Patients with psoriasis have a higher frequency of established CVD risk factors such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, the metabolic syndrome and they tend to smoke more.21–24 The reason for this high frequency of CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis is not fully understood. Are traditional CVD risk factors actually risk factors for both psoriasis and CVD? Or could it be a matter of reverse causation, meaning that psoriasis, due to its large negative impact on the quality of life, could lead to use of unhealthy stimuli? Shared genetics could also be part of the explanation. Most findings regarding psoriasis and CVD risk factors are results from observational studies. Inherent limitations of observational studies are confounding and reverse causation25, even though matching and statistical adjustments try to compensate for these limitations. Thus, associations and correlations can be found in observational studies; however, causal relationships are more difficult to prove. Recently, the causal relationships between psoriasis, the many CVD risk factors and comorbidities have been explored in Mendelian randomization (MR) studies.26–31 The MR approach is based on Mendel´s law of inheritance and uses the fact that genetic variants are randomly distributed during conception25,32–34, and in this way imitating the randomized controlled trial (Figure 1). By using genetic variants as a surrogate (instrumental variable) for a modifiable exposure, e.g., lifestyle factors, to examine the effect on a specific disease (e.g., psoriasis), confounding and reverse causation are less likely to occur. In situations where the randomized controlled trial cannot be conducted, the MR-study can be a valuable tool. For instance, several MR-studies have shown a causal relationship between obesity and psoriasis.26,29 These results support previous observational findings, e.g., that weight loss reduces the severity of psoriasis.35,36 There are possible limitations in MR-studies33, and findings from MR-studies should be interpreted in the context of other observational studies. In addition, findings should also be confirmed by more MR-studies. For example, one MR study have found that smoking is a causal risk factor for psoriasis29; however, these findings could not be confirmed in another MR study.37

Figure 1

Description automatically generated with medium confidence" />

Figure 1. Randomized controlled trial vs. Mendelian randomization

The Mendelian randomization (MR) design uses the fact that genetic variants are randomly distributed during conception. Confounders are therefore equally disseminated in the group without the genetic variant (non-carriers) versus the group with the genetic variant (carriers). The MR study therefore imitates the randomized controlled trials.

So why do patients with psoriasis have increased risk of cardiovascular disease?

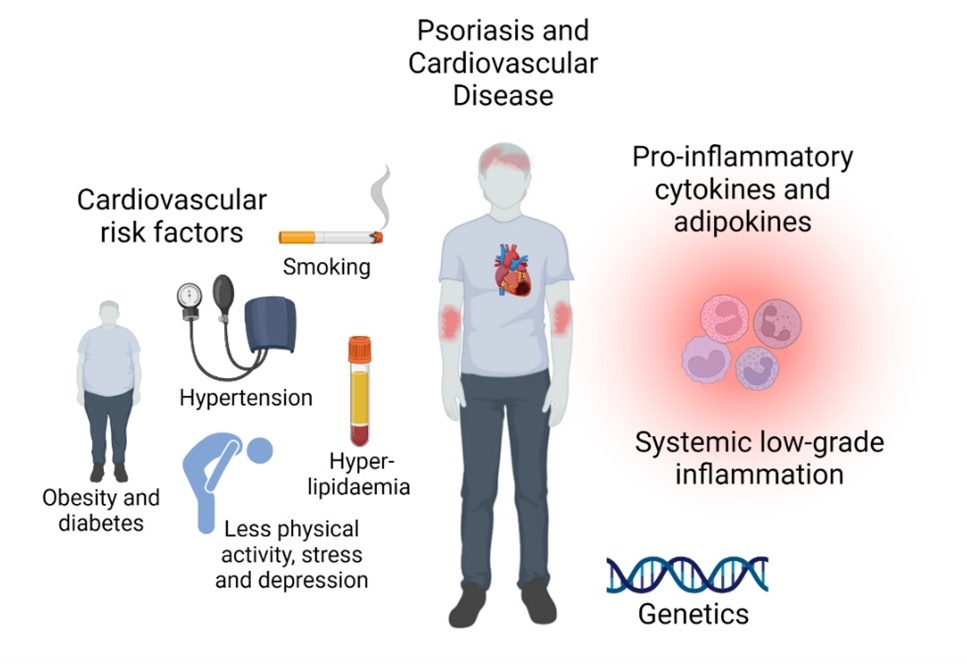

The possible mechanisms of the increased risk of CVD in patients with psoriasis are still discussed and the exact mechanisms are not fully understood. Several studies suggest that psoriasis itself is an independent risk factor of CVD after adjusting for other potential risk factors8,38,39. This has recently been confirmed by MR-studies.29,40 Inflammation is not only restricted to the skin in patients with psoriasis, and a state of chronic systemic low-grade inflammation occurs in these patients which may in part contribute to the increased risk of CVD.41 This is supported by increased levels of blood inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein.42 In addition, T-helper (Th)-1 and Th-17 cells are both activated in psoriasis and atherosclerosis, and important immunologic mediators including e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin (IL)-23, IL-17 and interferon (IFN)-γ are involved in the process of atherosclerotic and psoriatic plaques.43,44 Furthermore, many of these important cytokines as well as adipokines enhance insulin resistance and can thereby cause endothelial dysfunction.45 Indeed, many studies have suggested common immunologic pathways between the two diseases, but the potential shared genetics between psoriasis and CVD are less explored.46,47 Interestingly, a recent MR-study found shared genetic risk factors between psoriasis and coronary artery disease, and that coronary artery disease may have a causal effect on developing psoriasis, indicating that atherosclerotic disease could also be a trigger for developing psoriasis.48 In conclusion, the increased risk of CVD is most likely caused by a combination of a psoriasis-induced activated immune system, shared genetics, and co-existing CVD risk factors (Figure 2).5

Figure 2

Description automatically generated" />

Figure 2. Why do patients with psoriasis have increased risk of cardiovascular disease?

The increased risk of cardiovascuæar disease is most likely caused by a combination of systemic low-grade inflammation, shared genetics, and co-existing cardiovascular risk factors.

How can we help our patients?

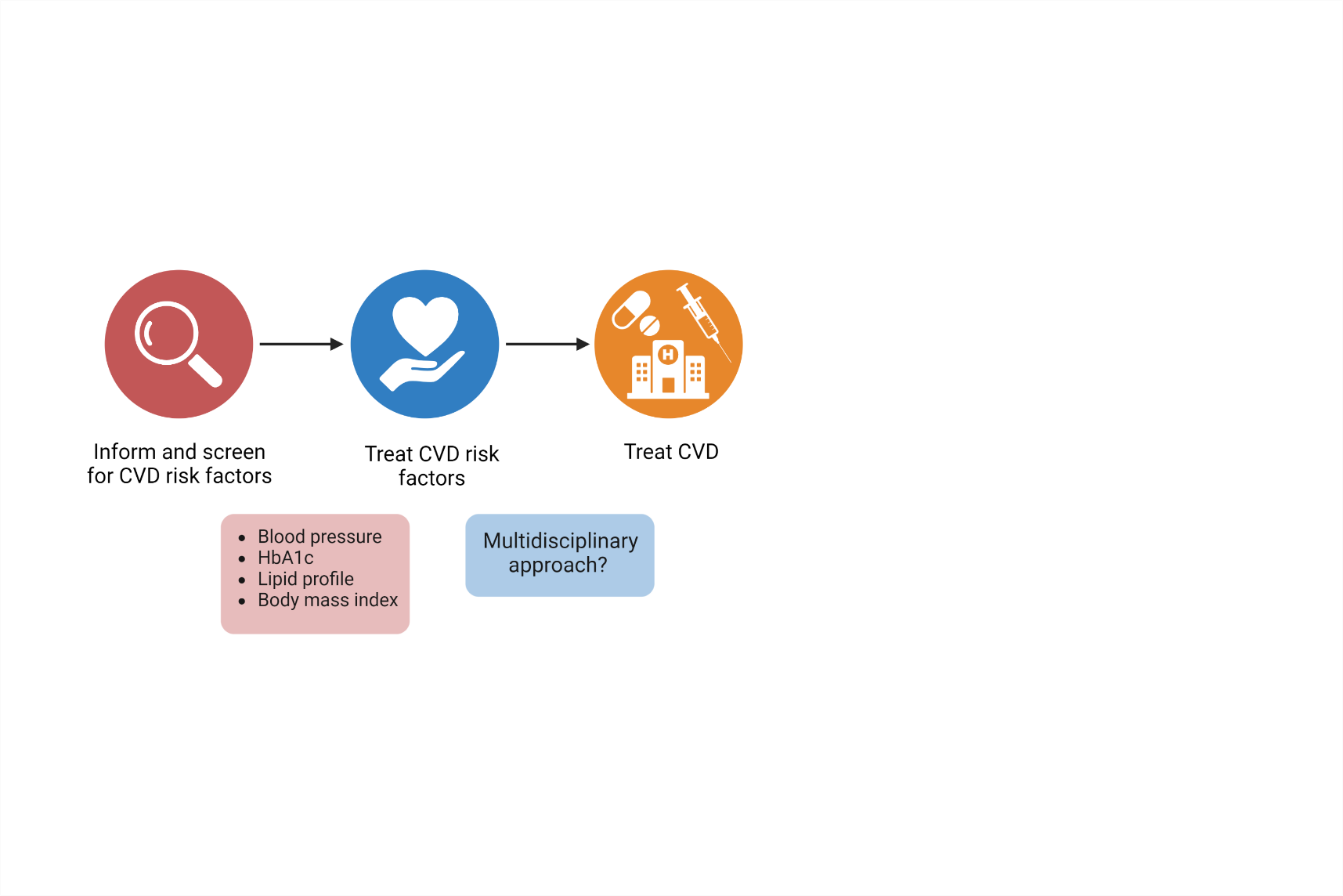

There are different considerations when screening and treating CVD risk factors in patients with psoriasis. Guidelines with the intention to identify these factors, in order to prevent CVD, vary and do not necessarily guide the physician sufficiently when facing patients with psoriasis. Additionally, it seems as there is no definite agreement whether psoriasis itself should be considered a risk factor. The joint guidelines provided by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) highlight the importance to integrate psoriasis in CVD risk management and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association indicate that psoriasis should be considered as a risk-enhancing factor.49,50 Moreover, the AAD/NPF guidelines suggest that we use a 1.5 multiplication factor when the risk of CVD is calculated in these patients.49 The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines also describe the principles and recommendations of how to handle the increased risk of CVD in patients with inflammatory joint diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis.51 But in guidelines to prevent CVD by the European Society of Cardiology, psoriasis is only briefly mentioned as a disease that may have potential to increase the risk of CVD and seemingly with no further guidance.52 Therefore, it depends on which guidelines different physicians (e.g., dermatologists, rheumatologists, or general practitioner) follow, and this will affect the results of potential CVD prevention and treatment for these patients. Notably, to reduce the risk of CVD in patients with psoriasis, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended and the physicians are suggested to screen these patients on a regular basis at least for lipid profile, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), blood pressure and anthropometrics such as body mass index (BMI) (Figure 3).53 Although previous studies have indicated that patients with psoriasis are undertreated for their CVD risk factors, a recent Danish study show that patients with psoriasis do not receive less pharmacological treatment for CVD risk factors compare to the general population.53–55 Data on the effect of anti-psoriatic treatment on the risk of CVD in patients with psoriasis are inconsistent. Hypothetically, reduced inflammation in the psoriatic lesions could lead to a reduced systemic inflammatory response and thereby reducing the risk of CVD, especially considering the results from the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study (CANTOS). This study found that Canakinumab, an anti-inflammatory drug targeting interleukin-1β, reduced the rate of recurrent cardiovascular events in patients with previous myocardial infarction.56 In patients with psoriasis, epidemiological studies indicate that TNF-α inhibitors and methotrexate (MTX) reduce the risk of CVD compared to other anti-psoriatic treatments. In line with this, TNF-α inhibitors have also been linked with reduced coronary artery inflammation in psoriatic patients.57–59 However, meta-analyses based on imaging studies that examine the effect of biologic treatment on vascular inflammation detected by PET/CT do not confirm these results.60,61 Currently, we lack well-designed randomized clinical trials designed for the purpose to better evaluate the effect of anti-psoriatic treatments on the risk of CVD in patients with psoriasis, especially with clinical endpoints.

Figure 3

Description automatically generated with medium confidence" />

Figure 3. How can we help our patients to avoid cardiovascular disease?

Clinical considerations regarding identification and screening for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in patients with psoriasis. Hba1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Psoriasis and liver disease

It all began with methotrexate…

Historically, the interest of liver disease in patients with psoriasis began in the 60´s when MTX was introduced in the treatment of psoriasis. MTX was first approved for the treatment of psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1972; however, it has been used off-label in the form of aminopterin since 1951.62 The rare complication of liver fibrosis during treatment with MTX was previously described from patients with leukaemia; however, these patients received a much larger dosage of MTX and were evidently suffering from a more generalized severe disease.63 Early case reports and case series from patients with psoriasis treated with MTX showed abnormal serum transaminases63, and smaller retrospective studies reported permanent liver damages.64 Since then, many studies have addressed this issue because MTX has been first-line therapy for patients with inadequate response to topical treatment.49,65 Most of the studies have found an reversible increase in serum transaminases, but the risk of liver fibrosis has been difficult to quantify.49,66,67

… but now everyone is talking about metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease

During the last 15 years, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease68, has been suggested as an important reason for the increased risk of liver fibrosis in patients with psoriasis. MASLD is currently the most common form of liver disease worldwide, affecting approximately 25% of the general population.69 Risk factors for developing MASLD includes e.g., obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, the metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance.70 MASLD is associated with both cardiovascular71 and liver-specific morbidity and mortality. MASLD is a continuum ranging from simple steatosis, which is harmless, to steatohepatitis (MASH)with steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning.72 MASH can lead to liver fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In the early stages of MASLD the disease is reversible; however, in the later stages with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, treatment is merely symptomatic.72 Treatment in early stages of MASLD include weight loss, physical activity, optimal treatment of other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and type 2 diabetes. No pharmacological agents are approved for treatment of MASLD but vitamin E and pioglitazone are used off-label for patients with significant fibrosis.72 Several randomized controlled trials testing new pharmacological agents are currently ongoing, with promising results for glucagon-like peptid-1 receptor agonists, which reduces steatosis by inducing weight loss.73

Because the disease is reversible in the beginning, early detection is crucial but difficult.

Serum transaminases can be affected but are actually normal in 80% of patients with steatosis.72 Clinical symptoms will often first appear in the very late stages with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Gold standard to diagnose MASLD is a liver biopsy74; however, this is an invasive procedure with potential serious side effects. In addition, the procedure requires hospitalization, which means it is time-consuming for the patient and the healthcare system. Because simple steatosis and MASH without fibrosis are rather harmless, non-invasive methods to find patients with sign of liver fibrosis have a great clinical significance. Several non-invasive alternatives exist; biomarkers such as Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) or NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS), and imagine techniques such as MR-elastography and controlled-vibration transient elastography (often assed by a Fibroscan®).74 These non-invasive techniques enable exclusion of patients without sign of liver fibrosis, saving the liver biopsy only for patients with sign of liver fibrosis in the non-invasive techniques.

Psoriasis and the liver – it´s complicated.

The first case series of three patients with concurrent psoriasis and steatohepatitis was published in 2001.75 In 2009, larger case-control studies were published.76,77 Gisondi and colleagues77 compared 130 patients with psoriasis with 260 healthy controls matched on sex, age, and BMI. They found MASLD (simple steatosis) in 47% of the patients with psoriasis and in 28% of the healthy controls. Some years later, larger population-based studies were published, confirming the association between psoriasis and MASLD, also after adjusting for potential confounders e.g., obesity and metabolic syndrome.78,79 Bellinato and colleagues summarized existing literature in a systemic review and meta-analysis including 15 studies, concluding that MASLD was more prevalent in patients with psoriasis compared to non-psoriatic controls, and patients with MASLD and psoriasis had a more severe form of psoriasis than patients with psoriasis without MASLD.80 Furthermore, they reported that patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis had the greatest risk for MASLD. However, most of these studies were cross-sectional and therefore merely reporting a correlation and not necessarily a causal relationship. In addition, the diagnosis of MASLD was for most of these studies based on simple steatosis. More interesting would be to examine the prevalence of MASLD with fibrosis, as described earlier.

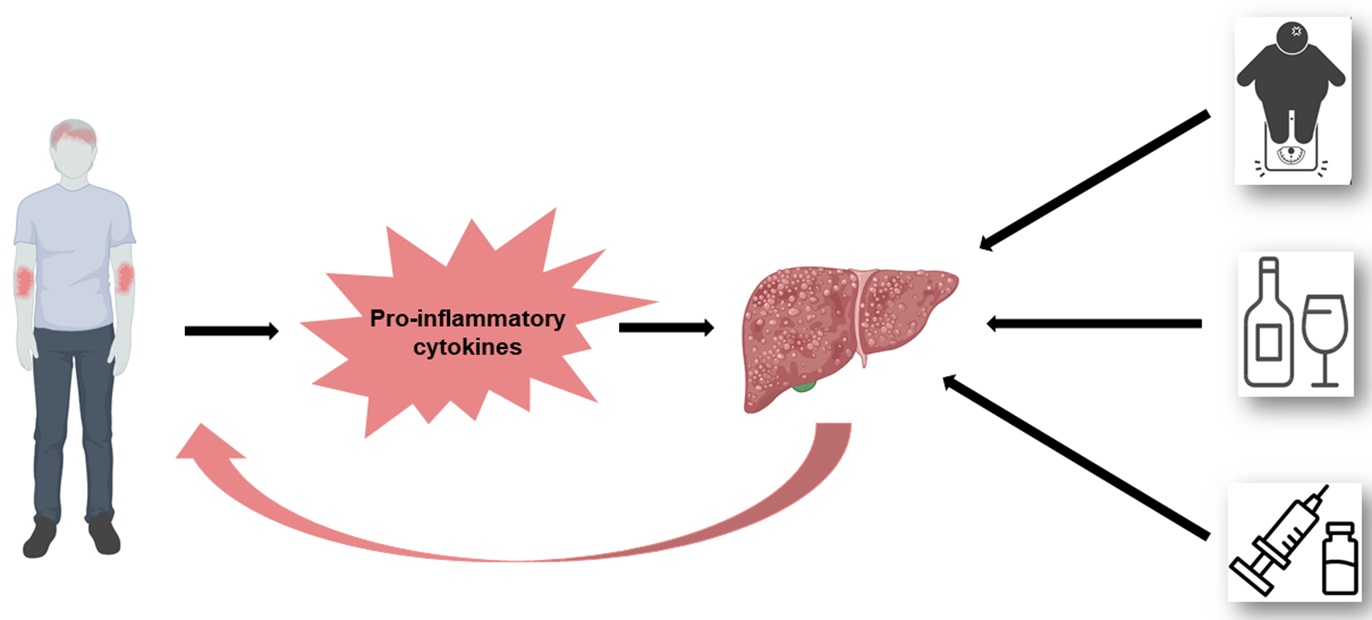

Some studies have also estimated the risk of incident liver disease (including MASLD)81, including subgroups of patients receiving systemic therapy82,83, supporting the results from above-mentioned studies. However, future large prospective studies are needed to understand the causal relationship between psoriasis and MASLD better. Theoretically, a causal relationship could be possible. The pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α) driving the inflammation in psoriasis could aggravate the development of MASLD, also suggested as the hepato-dermal axis.84 Similarly, pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by the liver could subsequently worsen the skin symptoms, potentially explaining why patients with both MASLD and psoriasis have a more severe disease than patients with psoriasis without MASLD. Recently, two MR-studies could not find evidence for a causal relationship between psoriasis and NAFLD.29,31 These results indicate that the observational association between psoriasis and MASLD is a result of shared confounding factors, such as e.g., obesity. Obesity is the strongest risk factor for MASLD, and have also been established as a causal risk factor for psoriasis.26,29 Moreover, another important potential confounder is alcohol consumption. A diagnosis of MASLD requires that the patient do not have an excessive alcohol consumption.72 However, alcohol consumption is always self-ported and there may be overlap and misclassifications between patients with MASLD and with alcoholic liver disease. Patients with psoriasis have a higher alcohol consumption than the general population, so this could indeed be an important confounder.85 Interestingly, among MTX users, patients with psoriasis have a higher risk of developing liver disease compared to patients with RA.83 This could be due to the higher BMI found in patients with psoriasis86, a possible difference in how the inflammation in psoriasis vs. RA affects the liver/interacts with MTX, or a combination.83 In conclusion, the total burden of risk factors for developing liver fibrosis is larger in patients with psoriasis compared to individuals without psoriasis, including systemic inflammation, obesity, alcohol consumption, and the use of MTX (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Description automatically generated" />

Psoriasis and liver disease - a complicated association

The total burden of risk factors for developing liver fibrosis is large in patients with psoriasis.

The pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α) driving the inflammation in psoriasis could aggravate the development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Similarly, pro-inflammatory cytokines produced by the liver could subsequently worsen the skin symptoms (the hepato-dermal axis). Furthermore, patients with psoriasis are often more obese than the general population, drink more alcohol, and many patients with moderate to severe psoriasis receive methotrexate (which can be hepatotoxic).

What can we do to help our patients with psoriasis?

Dermatologists still focus on the risk of liver disease due to the use of MTX; however, there are no international consensus on how to monitor these patients. AAD suggests an algorithm including non-invasive serologic tests at baseline (e.g., FIB-4), liver function tests every 3-6 months, and if necessary, assessing the liver stiffness with for example Fibroscan®.49 In Europe, some countries measure procollagen type III N-terminal peptide (P3NP) at baseline and every 6 months to detect patients with potential hepatotoxic side effects.87 Furthermore, there is increasing evidence suggesting that the clinical focus should be on metabolic risk factors (e.g. obesity, type 2 diabetes) instead because these confer a much larger risk of developing liver disease than MTX. International consensus of how to detect and monitor patients with psoriasis, and not only patients using MTX, are needed. More studies examining non-invasive biomarkers and assessment of liver stiffness are required to reach a consensus on how to detect and monitor different subgroups of these patients. In the meantime, we should consider the metabolic risk factors just as important, or even more, than MTX when assessing the risk of developing liver disease. Prevention and treatment of metabolic lifestyle factors have never been more important, aiming to reduce both the severity of the skin symptoms and the risk of comorbidities.

REFERENCES

1. Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: Epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76:377–90.

2. Karmacharya P, Chakradhar R, Ogdie A. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis: A literature review. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2021;35 10.1016/J.BERH.2021.101692.

3. Daugaard C, Iversen L, Hjuler KF. Comorbidity in Adult Psoriasis: Considerations for the Clinician. Psoriasis (Auckland, NZ) 2022;12:139–50 10.2147/PTT.S328572.

4. World Health Organization: The top 10 causes of death. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. Accessed 7 Mar 2023.

5. Garshick MS, Ward NL, Krueger JG, Berger JS. Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Psoriasis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;77:1670–80 10.1016/J.JACC.2021.02.009.

6. Salahadeen E, Torp-Pedersen C, Gislason G, Hansen PR, Ahlehoff O. Nationwide population-based study of cause-specific death rates in patients with psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol 2015;29:1002–5.

7. C J McDonald PC. Occlusive vascular disease in psoriatic patients. N Engl J Med 1973;288:912.

8. Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. J Am Med Assoc 2006;296:1735–41 10.1001/jama.296.14.1735.

9. Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:2411–8 10.1038/jid.2009.112.

10. Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Charlot M, et al. Psoriasis is associated with clinically significant cardiovascular risk: A Danish nationwide cohort study. J Intern Med 2011;270:147–57 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02310.x.

11. Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Jorgensen CH, et al. Psoriasis and risk of atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke: a Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. Eur Hear J 2012;33:2054–64.

12. Egeberg A, Thyssen JP, Jensen P, Gislason GH, Skov L. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A nationwide cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97:819–24 10.2340/00015555-2657.

13. Hjuler KF, Gormsen LC, Vendelbo MH, Egeberg A, Nielsen J, Iversen L. Increased global arterial and subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:732–40.

14. Kaiser H, Kvist-Hansen A, Krakauer M, et al. Association between Vascular Inflammation and Inflammation in Adipose Tissue, Spleen, and Bone Marrow in Patients with Psoriasis. Life (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;11 10.3390/LIFE11040305.

15. Balci DD, Balci A, Karazincir S, et al. Increased carotid artery intima-media thickness and impaired endothelial function in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:1–6.

16. Armstrong EJ, Harskamp CT, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis and major adverse cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of the American Heart Association 2013;2 10.1161/JAHA.113.000062.

17. Samarasekera EJ, Neilson JM, Warren RB, Parnham J, Smith CH. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in individuals with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:2340–6.

18. Miller IM, Ellervik C, Yazdanyar S, Jemec GBE. Meta-analysis of psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and associated risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:1014–24 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.053.

19. Liu L, Cui S, Liu M, Huo X, Zhang G, Wang N. Psoriasis Increased the Risk of Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes: A New Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Study. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9.

20. Kaiser H, Abdulla J, Henningsen KMA, Skov L, Hansen PR. Coronary artery disease assessed by computed tomography in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatology 2019;235:478–87.

21. Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and Obesity. Dermatology 2017;232:633–9.

22. Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA dermatology 2013;149:84–91 10.1001/2013.jamadermatol.406.

23. Khalid U, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, et al. Psoriasis and new-onset diabetes: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2402–7.

24. Prey S, Paul C, Bronsard V, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with plaque psoriasis: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2010;24 SUPPL. 2:23–30 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03564.x.

25. Davies NM, Holmes M V., Davey Smith G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ 2018;362 10.1136/BMJ.K601.

26. Budu-Aggrey A, Brumpton B, Tyrrell J, et al. Evidence of a causal relationship between body mass index and psoriasis: A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med 2019;16.

27. Wei J, Zhu J, Xu H, et al. Alcohol consumption and smoking in relation to psoriasis: a Mendelian randomization study. Br J Dermatol 2022 10.1111/bjd.21718.

28. Xiao Y, Jing D, Tang Z, et al. Serum lipids and risk of incident psoriasis: a prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank study and Mendelian randomization analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2022 10.1016/j.jid.2022.06.015.

29. Zhao SS, Bellou E, Verstappen SMM, et al. Association between psoriatic disease and lifestyle factors and comorbidities: cross-sectional analysis and Mendelian randomisation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022 10.1093/rheumatology/keac403.

30. Freuer D, Linseisen J, Meisinger C. Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Both Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: A Bidirectional 2-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. JAMA dermatology 2022 10.1001/JAMADERMATOL.2022.3682.

31. Näslund-Koch C, Bojesen SE, Gluud LL, Skov L, Vedel-Krogh S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not a causal risk factor for psoriasis: A Mendelian randomization study of 108,835 individuals. Front Immunol 2022;13 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.1022460.

32. Lawlor DA, Harbord RM, Sterne JAC, Timpson N, Smith GD. Mendelian randomization: using genes as instruments for making causal inferences in epidemiology. Stat Med 2008;27:1133–63 10.1002/SIM.3034.

33. Davey Smith G, Hemani G. Mendelian randomization: genetic anchors for causal inference in epidemiological studies. Hum Mol Genet 2014;23:R89-98 10.1093/hmg/ddu328.

34. Evans DM, Davey Smith G. Mendelian Randomization: New Applications in the Coming Age of Hypothesis-Free Causality. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2015;16:327–50 10.1146/ANNUREV-GENOM-090314-050016.

35. Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Obesity, waist circumference, weight change, and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ health study II. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1670–5 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1670.

36. Jensen P, Zachariae C, Christensen R, et al. Effect of Weight Loss on the Cardiovascular Risk Profile of Obese Patients with Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol 2014;94:691–4.

37. Näslund-Koch C, Vedel-Krogh S, Bojesen SE, Skov L. Smoking is an independent but not a causal risk factor for moderate to severe psoriasis: A Mendelian randomization study of 105,912 individuals. Front Immunol 2023;14:737 10.3389/FIMMU.2023.1119144.

38. Gaeta M, Castelvecchio S, Ricci C, Pigatto P, Pellissero G, Cappato R. Role of psoriasis as independent predictor of cardiovascular disease: a meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:2282–8.

39. Coumbe AG, Pritzker MR, Duprez DA. Cardiovascular risk and psoriasis: beyond the traditional risk factors. Am J Med 2014;127:12–8.

40. Gao N, Kong M, Li X, et al. The Association Between Psoriasis and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front Immunol 2022;13:918224 10.3389/fimmu.2022.918224.

41. Boehncke WH. Systemic inflammation and cardiovascular comorbidity in psoriasis patients: Causes and consequences. Frontiers in Immunology 2018;9 APR 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00579.

42. Dowlatshahi EA, van der Voort EAM, Arends LR, Nijsten T. Markers of systemic inflammation in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2013;169:266–82.

43. Hansson GK, Robertson AKL, Söderberg-Nauclér C. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2006;1:297–329.

44. Harrington CL, Dey AK, Yunus R, Joshi AA, Mehta NN. Psoriasis as a human model of disease to study inflammatory atherogenesis. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol 2017;312:H867-h873.

45. Boehncke W-H, Boehncke S, Tobin A-M, Kirby B. The “psoriatic march”: a concept of how severe psoriasis may drive cardiovascular comorbidity. Exp Dermatol 2011;20:303–7 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01261.x.

46. Lu Y, Chen H, Nikamo P, et al. Association of cardiovascular and metabolic disease genes with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:836–9.

47. Koch M, Baurecht H, Ried JS, et al. Psoriasis and cardiometabolic traits: modest association but distinct genetic architectures. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:1283–93.

48. Patrick MT, Li Q, Wasikowski R, et al. Shared genetic risk factors and causal association between psoriasis and coronary artery disease. Nat Commun 2022;13:6565 10.1038/S41467-022-34323-4.

49. Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:1073–113 10.1016/J.JAAD.2018.11.058.

50. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–646.

51. Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:17–28.

52. Visseren FLJ, MacH F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3227–337.

53. Garshick MS, Berger JS. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Disease-An Ounce of Prevention Is Worth a Pound of Cure. JAMA dermatology 2022;158:239–41.

54. Eder L, Harvey P, Chandran V, et al. Gaps in Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Patients with Psoriatic Disease: An International Multicenter Study. J Rheumatol 2018;45:378–84.

55. Liljendahl MS, Loft N, Passey A, Wegner S, Egeberg A, Skov L. Pharmacological treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis: A Danish nationwide study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2023.

56. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–31 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914.

57. Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, et al. Cardiovascular disease event rates in patients with severe psoriasis treated with systemic anti-inflammatory drugs: a Danish real-world cohort study. J Intern Med 2013;273:197–204 10.1111/J.1365-2796.2012.02593.X.

58. Ahlehoff O, Skov L, Gislason G, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes and systemic anti-inflammatory drugs in patients with severe psoriasis: 5-year follow-up of a Danish nationwide cohort. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015;29:1128–34.

59. Elnabawi YA, Oikonomou EK, Dey AK, et al. Association of biologic therapy with coronary inflammation in patients with psoriasis as assessed by perivascular fat attenuation index. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:885–91.

60. Kleinrensink NJ, Pouw JN, Leijten EFA, et al. Increased vascular inflammation on PET/CT in psoriasis and the effects of biologic treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Transl Imaging 2022.

61. González-Cantero A, Ortega-Quijano D, Álvarez-Díaz N, et al. Impact of biologic agents on imaging and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Invest Dermatol 2021.

62. Czarnecka-Operacz M, Sadowska-Przytocka A. The possibilities and principles of methotrexate treatment of psoriasis - the updated knowledge. Postep dermatologii i Alergol 2014;31:392–400 10.5114/PDIA.2014.47121.

63. MG D. Methotrexate and the liver. Br J Dermatol 1969;81:465–7 10.1111/J.1365-2133.1969.TB14021.X.

64. Dahl MGC, Gregory MM, Scheuer PJ. Liver damage due to methotrexate in patients with psoriasis. Br Med J 1971;1:625–30 10.1136/BMJ.1.5750.625.

65. Psoriasis: assessment and management. 2017https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

66. Whiting-O’Keefe QE, Fye KH, Sack KD. Methotrexate and histologic hepatic abnormalities: A meta-analysis. Am J Med 1991;90:711–6.

67. Maybury CM, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Wong T, Dhillon AP, Barker JN, Smith CH. Methotrexate and liver fibrosis in people with psoriasis: a systematic review of observational studies. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:17–29 10.1111/BJD.12941.

68. Rinella ME, Lazarus J V., Ratziu V, et al. A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. 2023.

69. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84 10.1002/hep.28431.

70. Cotter TG, Rinella M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease 2020: The State of the Disease. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1851–64 10.1053/J.GASTRO.2020.01.052.

71. Mahfood Haddad T, Hamdeh S, Kanmanthareddy A, Alla VM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the risk of clinical cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev 2017;11:S209–16.

72. Marchesini G, Day CP, Dufour JF, et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64:1388–402 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.11.004.

73. Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Csermely A, Lonardo A, Targher G. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Metabolites 2021;11:1–13 10.3390/METABO11020073.

74. Drescher HK, Weiskirchen S, Weiskirchen R. Current Status in Testing for Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Cells 2019;8 10.3390/CELLS8080845.

75. Lonardo A, Loria P, Carulli N. Concurrent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and psoriasis. Report of three cases from the POLI.ST.E.N.A. study. Dig Liver Dis 2001;33:86–7 10.1016/S1590-8658(01)80144-4.

76. Miele L, Vallone S, Cefalo C, et al. Prevalence, characteristics and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J Hepatol 2009;51:778–86 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.06.008.

77. Gisondi P, Targher G, Zoppini G, Girolomoni G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J Hepatol 2009;51:758–64 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.020.

78. Tsai T-F, Wang T-S, Hung S-T, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidities of psoriasis patients in a national database in Taiwan. J Dermatol Sci 2011;63:40–6 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.002.

79. van der Voort EAM, Koehler EM, Dowlatshahi EA, et al. Psoriasis is independently associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients 55 years old or older: Results from a population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:517–24 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.044.

80. Bellinato F, Gisondi P, Mantovani A, Girolomoni G, Targher G. Risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Endocrinol Invest 2022;45:1277–88 10.1007/s40618-022-01755-0.

81. Ogdie A, Grewal SK, Noe MH, et al. Risk of Incident Liver Disease in Patients with Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis, and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Study. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138:760–7.

82. Munera-Campos M, Vilar-Alejo J, Rivera R, et al. The risk of hepatic adverse events of systemic medications for psoriasis: a prospective cohort study using the BIOBADADERM registry. J Dermatolog Treat 2021;:1–28 10.1080/09546634.2021.1922572.

83. Gelfand JM, Wan J, Zhang H, et al. Risk of liver disease in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate: A population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021;84:1636–43 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.019.

84. Mantovani A, Gisondi P, Lonardo A, Targher G. Relationship between Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Psoriasis: A Novel Hepato-Dermal Axis? Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:217 10.3390/ijms17020217.

85. Brenaut E, Horreau C, Pouplard C, et al. Alcohol consumption and psoriasis: A systematic literature review. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2013;27 SUPPL.3:30–5 10.1111/jdv.12164.

86. Radner H, Lesperance T, Accortt NA, Solomon DH. Incidence and Prevalence of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis, Psoriasis, or Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1510–8 10.1002/ACR.23171.

87. Raaby L, Zachariae C, Østensen M, et al. Methotrexate use and monitoring in patients with psoriasis: A consensus report based on a danish expert meeting. Acta Derm Venereol 2017;97:426–32 10.2340/00015555-2599.

Posted on

« Comorbidity in adult psoriasis Next Article

Topical gene therapy for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa »

Related Articles

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

HEAD OFFICE

Laarderhoogtweg 25

1101 EB Amsterdam

The Netherlands

T: +31 85 4012 560

E: publishers@medicom-publishers.com