Prof. Stephen L. Hauser is a professor of the Department of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), USA. His work specializes in immune mechanisms and multiple sclerosis (MS). Hauser trained in internal medicine at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, in neurology at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and in immunology at Harvard Medical School and the Institute Pasteur in Paris, France, and was a faculty member at Harvard Medical School before moving to UCSF. He has contributed to the establishment of consortia that have identified more than 50 gene variants that contribute to MS risk.

Prof. Stephen L. Hauser is a professor of the Department of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), USA. His work specializes in immune mechanisms and multiple sclerosis (MS). Hauser trained in internal medicine at the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, in neurology at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), and in immunology at Harvard Medical School and the Institute Pasteur in Paris, France, and was a faculty member at Harvard Medical School before moving to UCSF. He has contributed to the establishment of consortia that have identified more than 50 gene variants that contribute to MS risk.In August 2020, the fully human anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody ofatumumab was approved for the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). In the open-label extension study ALITHIOS (NCT03650114), ofatumumab's safety profile was shown to be consistent with data from the core phase 3 ASCLEPIOS I/II trials (NCT02792218 and NCT02792231).

Ofatumumab data

Ofatumumab is a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody whose epitope is distinct from that of rituximab, with a stronger affinity, and with a slower off-rate. It causes cytotoxicity in the cells that express CD20 by means of complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity 1. One preclinical study reported a potent and rapid reduction of B cells along with a simultaneous drop in CD20+ T cell counts as a result of anti-CD20 antibody action in Cynomolgus monkeys treated with human equivalent doses of subcutaneous ofatumumab 2. The rationale behind trying ofatumumab for the treatment of MS was was based on previous data supporting that anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies that induce B-cell depletion, such as rituximab and ocrelizumab, are effective disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis 3-6.

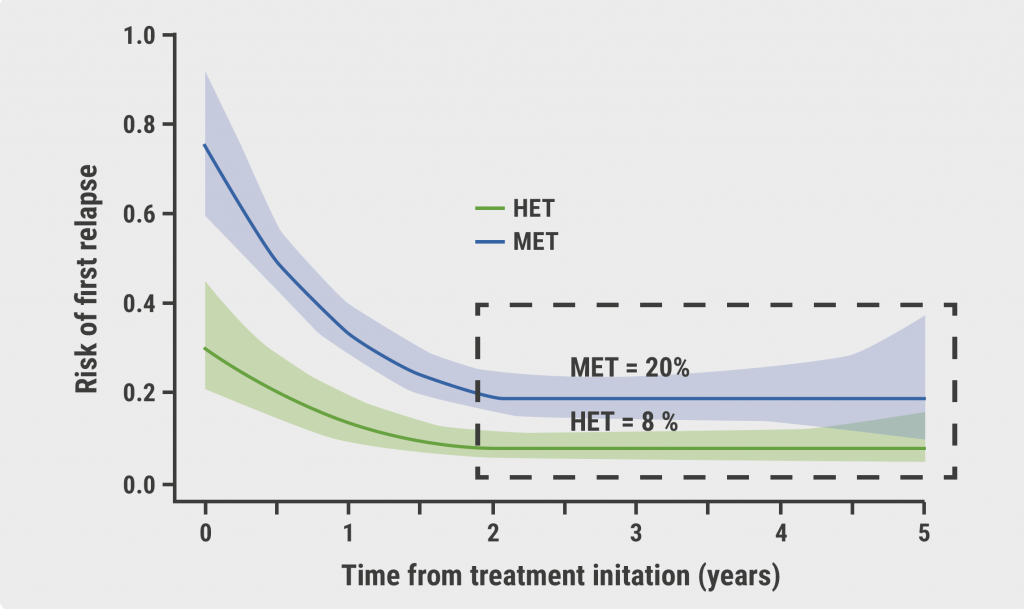

We recently published the results of the ASCLEPIOS trials, in which ofatumumab demonstrated superior efficacy versus teriflunomide and a favorable safety profile in relapsing MS patients. Ofatumumab reduced the annualized relapse rate by 51% (0.11 vs 0.22) and 58% (0.10 vs 0.25) in ASCLEPIOS I and II, respectively (P<0.001 in both studies)7. Long-term safety data from these cohorts continues to be collected within the open-label phase 3b ALITHIOS extension study, which was reported at MSVirtual2020 in September 8.

Participants came from three sources (n=1,230): patients who were randomized to ofatumumab in the phase 2 APLIOS (12 weeks) or phase 3 ASCLEPIOS I/II (up to 30 months) trials and continued in ALITHIOS (median duration of ofatumumab treatment: 21 months); patients who completed/discontinued the core study yet continued in the safety follow-up; and the patients (n=643) who were randomized to teriflunomide in ASCLEPIOS I/II and then crossed over to ofatumumab in ALITHIOS (median duration of ofatumumab treatment: 4.4 months). The overall exposure was 2,118 patient-years.

Overall safety at 2 years was promising. The most frequently reported adverse events (AEs) in ALITHIOS were injection-related reactions and upper respiratory tract infections. Most reported AEs were mild-to-moderate in severity. The overall safety profile was consistent with reports from the core ASCLEPIOS I/II trials. There were no deaths. In the cross-over group, injection-related reactions were mild-to-moderate; none were serious or led to treatment discontinuation. With regard to AEs of special interest, there were no opportunistic infections, hepatitis B reactivation, or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) events. Also, there were no new cases of malignancies in either the continuous or cross-over patients. This post-hoc analysis with safety extension data indicates that extended exposure to ofatumumab does not appear to pose increased risk, and opens the door for long-term use in MS patients.

Interpretation of these findings

The ASCLEPIOS studies found that ofatumumab produced a significant reduction in new inflammation, as well as fewer clinical relapses and progression events. These new data speak to the long-term safety profile of ofatumumab. This is one of the great success stories in modern molecular medicine.. There is a 99 percent effect size of B-cell therapies on new areas of scarring, new areas of sclerosis, and with that, relapses are brought down to extraordinarily low levels. What we have learned is that when we eliminate relapses, we can see progression in most people with MS from day 1, so-called “silent progression” 9,10. Now we recognize that the two faces of MS, a focal adaptive inflammatory component and a neurodegenerative component, aren’t distinct, but form a continuum. Plus, our ability to completely control new focal scarring and demyelination, has changed the way we can treat MS. The clinical goal is control of progression. Clinicians need to begin to pivot from a “treat-to-target” concept to more of a cancer model, where we think about concepts like inducing remission, with subsequent monitoring and maintenance. For neurodegenerative problems, complete remission would be elimination of disease progression above the surface but also below the surface. We can now begin to target the pathophysiology. An important take-home message is that we will judge these B-cell therapeutics by their efficacy in halting progressive disease, and the mode of administration will matter.

Next steps

Our ongoing hypothesis is that relapses are mediated by B-cells in the bloodstream and the periphery that migrate to the nervous system, and that progression is mediated by B-cells that are already in the nervous system and protected there in niches, ectopic lymphoid follicles. We are going to compare ofatumumab with ocrelizumab and other B-cell drugs on the horizon, as well as BTK inhibitors, and probably CD38 or CD19 inhibitors as well, based on how well they do against progression. We have solved the relapsing aspect of this disease. This is one of the enormous success stories of medicine; there are real advantages to ofatumumab because it is a fully human molecule and after the first dose there is no evidence of any injection reaction above the placebo comparator. The data indicate that the safety data are stable for at least two years, and overall, very tolerable.

Ultimately for relapsing patients, right-sizing the dose of B-cell therapy and understanding this concept of “treat maximally at onset” will deliver great benefit. The greatest effects against progression are going to happen down the road with regard to the drugs, the regimen, and the method of administration. Right now, all three of the FDA-approved anti-CD20 drugs are probably more or less equivalent with regard to progression In the next couple of years, researchers will really need to laser in on accelerating the efficacy against progression, improving the convenience for the patient, and confirm safety in extended cohorts.

Take home messages:

- The phase 3 ASCLEPIOS I/II demonstrated that ofatumumab treatment significantly reduced flaring in relapsing MS patients.

- The open-label extension study ALITHIOS trial showed that overall safety of ofatumumab at 2 years was promising.

- These B-cell therapeutics will be judged by their efficacy in halting progressive disease, and their mode of administration will matter.

- All three of the FDA-approved anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies are probably more or less equivalent with regard to progression. In the next couple of years, researchers will really need to laser in on accelerating the efficacy against progression, improving the convenience for the patient, and confirm safety in extended cohorts.

References

- Lin TS. Pharmgenomics Pers Med. 2010;3:51-9.

- Theil D, et al. Front Immunol. 2019 Jun 20;10:1340.

- Hauser SL, et al. N Engl J Med 2017;376:221-34.

- Hauser SL, et al. N Engl J Med 2008;358:676-88.

- Montalban X, et al. N Engl J Med 2017;376:209-20.

- Vermersch P, et al. Mult Scler 2014;20:705-16.

- Hauser SL, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:546–57.

- Cross AH, et al. MSVIRTUAL2020, Abstract P0234.

- Hauser SL. JAMA. 2020;324(9):841-842.

- Greenfield AL, Hauser SL. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(1):13-26.

Posted on

Previous Article

« How to avoid chemotherapy overtreatment in breast cancer Next Article

4-year PACIFIC data hold strong in NSCLC »

« How to avoid chemotherapy overtreatment in breast cancer Next Article

4-year PACIFIC data hold strong in NSCLC »

Related Articles

December 4, 2023

Anti-CD40L antibody safe and effective in a phase 2 study

December 4, 2023

Prioritising high efficacy therapies in children with MS

April 13, 2021

MS: EXCHANGE Trial Perspectives from Prof. Amit Bar-Or

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy