In recent years, tobacco use has increased largely by a rise in vaping in adolescents and young adults. “Industry claims that it is less harmful than smoking, but different studies have shown that most e-cigarette vapers will also use cigarettes,” explained Dr Vijay Chopra (Max Super Speciality Hospital Saket, India) [1]. Similar to cigarettes, e-cigarettes cause cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA strand shrinkage, dysregulation of gene expression, and mitochondrial dysgenesis. According to a position paper of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC), no direct randomised data is available on e-cigarettes in heart failure (HF) [2]. While the long-term direct cardiovascular effects of e-cigarettes remain largely unknown, the existing evidence suggests that the e-cigarette should not be regarded as a cardiovascular safe product. E-cigarettes are likely to increase cardiovascular risk because they lead to an increased heart rate, increased arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction. Moreover, they have been shown to increase blood pressure. Dr Chopra emphasised that “95% of all publications without a conflict of interest found a harmful effect of e-cigarettes compared with only 20% of sponsored publications by the vaping industry.”

One drink a day elevates the risk of AF

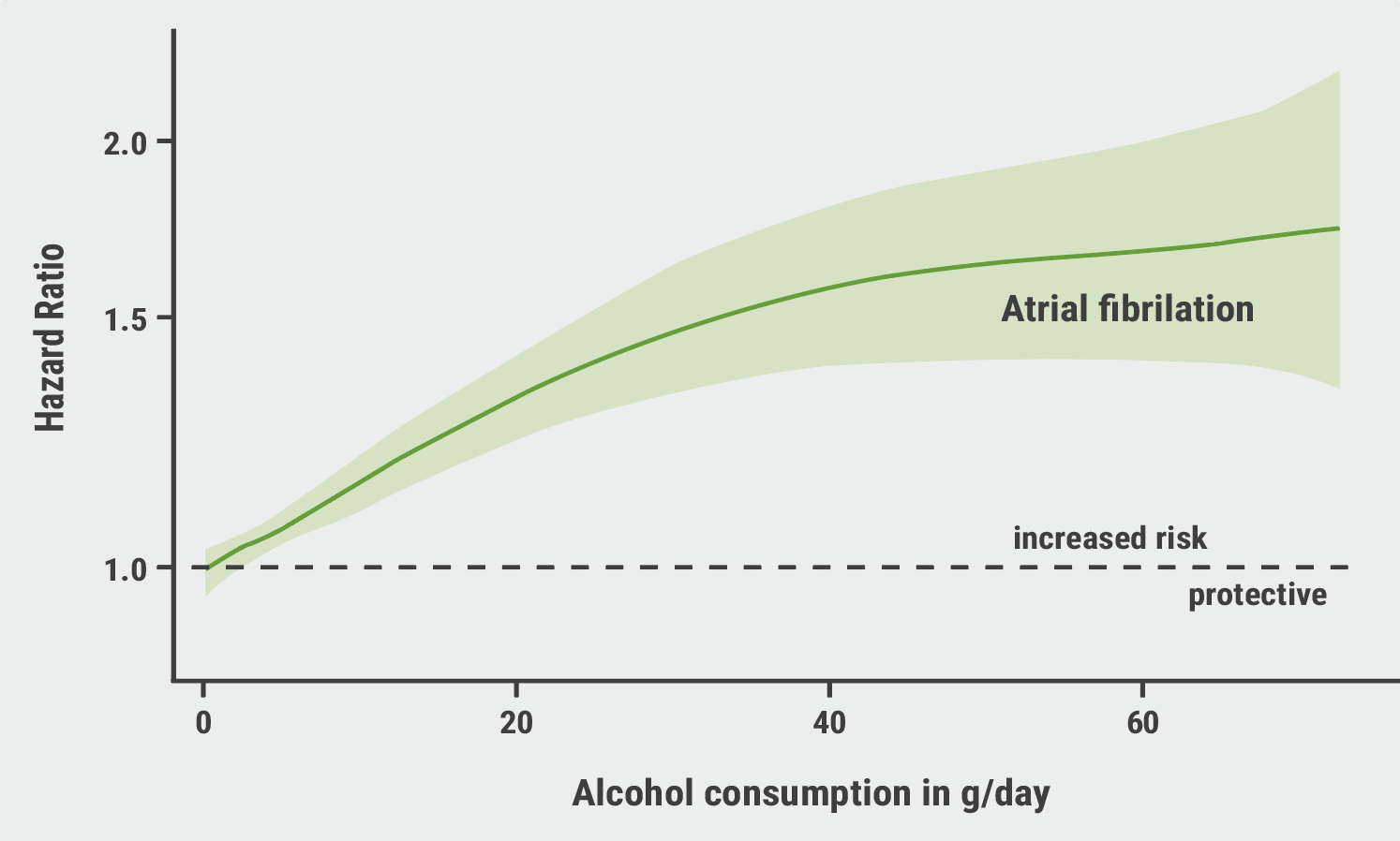

A meta-analysis published in 2006 showed a J-shaped relationship between alcohol and total mortality in both men and women. Consumption of alcohol, up to 4 drinks per day in men and 2 drinks per day in women, was inversely associated with total mortality, maximum protection being 18% in women and 17% in men [3]. A study published this year showed detrimental effects of small amounts of alcohol intake [4]. In a community-based cohort, 107,845 individuals were followed for the association between drink consumption and drinking patterns, and the incident of atrial fibrillation (AF). The hazard ratio for only 1 drink (12 g) per day was 1.16 (95% CI 1.11–1.22; P<0.001; see Figure). Associations were similar across types of alcohol. Dr Chopra pointed out that small amounts of alcohol are protective for HF, but the risk of AF increases even with small amounts of alcohol, which needs to be considered in AF prevention.

Figure: Alcohol consumption and incident atrial fibrillation [4]

Methamphetamine use is another increasing problem worldwide. Its use results in an acute, rapid increase in both heart rate and blood pressure. Chronic methamphetamine exposure leads to vasoconstriction, cerebral hypoperfusion, and an imbalance of circulatory vasoregulatory substances. Methamphetamine use has been associated with a partially reversible, inflammatory, dilated cardiomyopathy with HF with reduced ejection fraction and can also present as takotsubo cardiomyopathy [5]. Improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction is often seen after abstinence. The extent of myocardial fibrosis seems to predict the recoverability of left ventricular function. Similarly, cocaine use stimulates the sympathetic nervous system and different cardiac and vascular complications can result from its use [6]. It can also cause takotsubo-like cardiomyopathy, aortic dissection, and acute myocarditis. “The abuse of psychoactive substances is a significant preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in HF,” Dr Chopra concluded.

- Chopra VK. 21st century modern factors (alcohol, vaping, illicit drugs). Heart Failure and World Congress on Acute Heart Failure 2021, 29 June–1 July.

- Kavousi M, et al. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2020. Doi:10.1177/2047487320941993.

- Di Castelnuovo A, et al. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2437–45.

- Csengeri D, et al. Eur Heart J 2021;42:1170–7.

- Schürer St, et al. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:435–45.

- Kim ST, Park T. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:584.

Copyright ©2021 Medicom Medical Publishers

Posted on

Previous Article

« Heart failure patients might be at an increased risk for head and neck cancer Next Article

Biomarker panel predicts SGLT2 inhibitor response »

« Heart failure patients might be at an increased risk for head and neck cancer Next Article

Biomarker panel predicts SGLT2 inhibitor response »

Table of Contents: HFA 2021

Featured articles

Inconclusive results for dapagliflozin treatment in heart failure

Late-Breaking Trials

Iron substitution improves LVEF in intensively treated CRT patients with iron deficiency

Novel mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist effective irrespective of HF history

Iron substitution in iron-deficient HF patients is highly cost-effective

Omecamtiv mecarbil might be less effective in patients with atrial fibrillation or flutter

Vericiguat effective irrespective of atrial fibrillation status

Baroreflex activation: a novel option to improve heart failure symptoms

Beta-blocker withdrawal to enhance exercise capacity in heart failure?

Inconclusive results for dapagliflozin treatment in heart failure

Computerised cognitive training improves cognitive function in HF patients

COVID-19 and the Heart

COVID-19-related HF: from systemic infection to cardiac inflammation

Myocardial infarction outcomes were significantly affected by the pandemic

TAPSE effective biomarker associated with high-risk of severe COVID-19

COVID-19 in AF patients with HF: no higher mortality but longer hospital stay

Cancer and the Heart

Heart failure patients might be at an increased risk for head and neck cancer

Trastuzumab associated with cardiotoxicity in breast cancer

Heart Failure Prevention and HRQoL in the 21st century

Psychoactive substances put young people at risk of cardiovascular disease

The challenge of improving the quality of life of heart failure patients

SGLT2 Inhibitors in Heart Failure

Empagliflozin linked to lower cardiovascular risk and renal events in real-world study

Efficacy of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin not influenced by diabetes status

Biomarker panel predicts SGLT2 inhibitor response

Best of the Posters

Real-world study suggests sacubitril/valsartan benefits elderly patients with HF

Proenkephalin: A useful biomarker for new-onset heart failure?

Weight loss associated with increased mortality risk in heart failure patients

Echocardiographic parameters linked to dementia diagnosis

Related Articles

August 19, 2021

Biomarker panel predicts SGLT2 inhibitor response

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy