"Findings from our study can help clinicians counsel patients about the expected long-term risks and consequences of major bleeding, and inform shared decision-making about extended therapy," Faizan Khan, PhD candidate (epidemiology), University of Ottawa and Ottawas Hospital Research Institute, in Canada, told Reuters Health by email.

For patients with a first unprovoked proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) who have completed at least three to six months of initial anticoagulant treatment, the 2016 guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians and 2020 guidelines from the American Society of Hematology suggest continuing anticoagulation indefinitely over stopping it, except in patients deemed to be at high risk for major bleeding.

Khan and colleagues did a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the incidence of major bleeding during extended anticoagulant therapy (a minimum of six additional months after at least three months and up to five years).

The analysis included 14 randomized controlled trials and 13 cohort studies with more than 17,000 patients with a first unprovoked VTE, of whom 9,982 were treated with a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) and 7,220 with a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC).

The incidence of major bleeding per 100 person-years was 1.74 events with VKAs and 1.12 events with DOACs, a significant difference, the researchers report in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The five-year cumulative incidence of major bleeding with VKAs was 6.3% (95% confidence interval, 3.6% to 10.0%). The researchers lacked adequate data to estimate the incidence of major bleeding beyond one year of extended DOAC therapy.

For patients receiving extended treatment with either a VKA or a DOAC, the incidence of major bleeding was statistically significantly higher among people older than age 65, and among those with a creatinine clearance <50 mL/min, history of bleeding, concomitant use of an antiplatelet or a hemoglobin level <100 g/L.

"Our meta-analysis supports the existence of a clinically meaningful difference in long-term risk for anticoagulant-related major bleeding among patients with a first unprovoked VTE stratified according to presence or absence" of these risk factors, Dr. Khan and colleagues write.

The case fatality rate of major bleeding was 8.3% (95% CI, 5.1% to 12.2%) with VKAs and 9.7% (95% CI, 3.2% to 19.2%) with DOACs.

"Taken together, our results provide clinicians, patients, and policymakers with a management framework in which to consider the long-term risks for and consequences of major bleeding if anticoagulation is continued beyond the initial three to six months," the researchers say.

"When weighed against the long-term risks for and consequences of recurrent VTE if anticoagulation is discontinued, our results could be used to balance the benefits and harms of extended anticoagulation for unprovoked VTE," they add.

In a phone interview with Reuters Health, Dr. Omar Lattouf, cardiovascular surgeon at Mount Sinai Morningside in New York, who wasn't involved in the study, said it's "important and deserves our full attention."

"The dominant current way of thinking is that patients who have unprovoked pulmonary emboli should receive lifelong anticoagulation," Dr. Lattouf said.

"This analysis shows that there may be an increased risk of significant bleeding or slightly increased risk of death when you follow those patients for several years, five years or 10 years, and that the anticoagulation itself may cause slightly higher risk of major bleeding or death than not having a blood thinner," Dr. Lattouf said.

"Does this cause us to change our practice pattern? I think that's an open question that probably will be discussed further," he told Reuters Health.

"Certainly, it raises a red flag and will heighten our awareness," he added, particularly in patients who are typically considered at increased risk of complications and bleeding from anticoagulation, including patients who have a history of bleeding unrelated to anticoagulation, patients who are older than 65 years of age, and patients who have renal dysfunction or are anemic.

Dr. Lattouf said the question of prolonged anticoagulation is more complicated for the healthy young adult who is not at increased risk for bleeding and comes in with a near life-threatening pulmonary embolus.

"Questions on those patients have not been answered by this important publication and until we answer that I am more inclined to continue prolonged anticoagulation under continuous monitoring," Dr. Lattouf told Reuters Health.

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

SOURCE: https://bit.ly/3lq4UX0 Annals of Internal Medicine, online September 12, 2021.

By Megan Brooks

Posted on

Previous Article

« PCSK9 inhibitors may not be sufficient to curb atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Next Article

Triple therapy boosts survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer »

« PCSK9 inhibitors may not be sufficient to curb atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Next Article

Triple therapy boosts survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer »

Related Articles

October 30, 2023

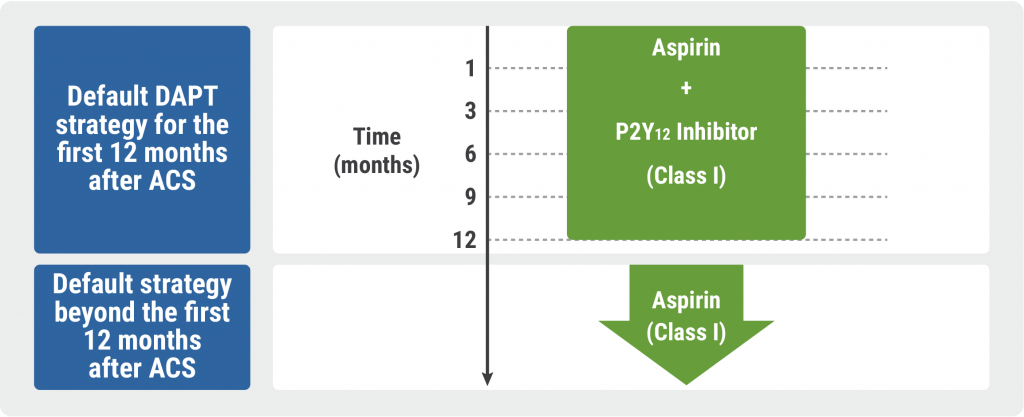

Guidelines for Acute Coronary Syndrome

September 8, 2020

Higher thrombotic risk in NSCLC patient with ALK rearrangement

© 2024 Medicom Medical Publishers. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy